Facing (Liturgical) East in the Anglican Tradition

Thread by @anglican_net on Thread Reader App – Thread Reader App

Clipped from: https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1777427532075180167.html

🧵 Anglican theology of “facing towards the East” (“ad orientem”)

-which way have Anglican ministers historically faced during the Divine Service?

-what theology underpins this?

-are there statistics that demonstrate the common practice?

Let’s explore 👇

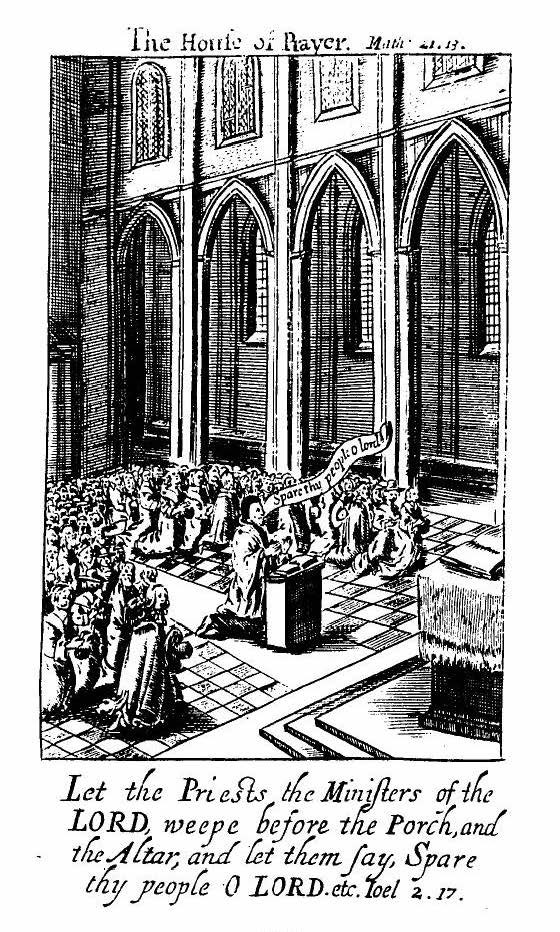

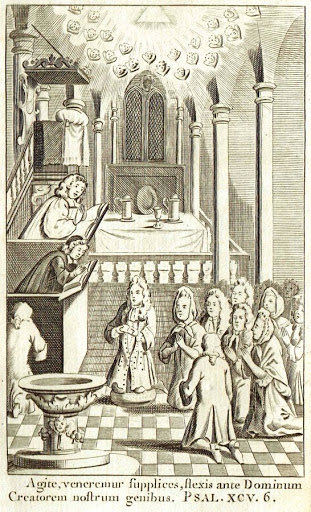

Image source: Thomas Cranmer, “Catechismus” (1548)

At the English Reformation, Anglican clerics celebrated the Divine Service facing eastward (see images above). This was in common with the Lutheran and medieval practice.

Lutheran Medieval

The Anglican directionality stemmed from a particular theology of the East, which informed which way the congregation and the minister faced, how burials were conducted and how the corpses were oriented, and even from which direction the people expected Christ’s Second Coming:

Elizabethan Confusion and the “North-side” Position

1540s patristic research uncovered many Church Fathers practicing holy communion not up in front of the congregation, but in their midst (with the priest still facing East). Therefore a BCP rubric instructed for the altar table to be brought among the people at Communion. To fit it in the nave, it had to be rotated lengthwise. In order for the priest to continue facing East, he stood at the narrow side (the “north end”). At the end of Communion, and at all other times, the altar table was to be returned to the chancel against the East wall.

At the accession of Queen Elizabeth I, some Puritan clerics began to clamour against a high view of the clergy, and opposed the priest facing away from the people. And they refused to return the altar table back to the chancel, always keeping it in the midst of the church.

Church authorities imposed discipline and mandated for the altar table to be kept in the chancel at all times other than at Holy Communion.

Eventually the practice of moving the altar table proved too cumbersome, and it was permanently kept in the chancel. But the Puritan clerics used the ambiguity in the rubric, and whilst keeping the altar table in the chancel, they still stood at its narrow edge! Thus they neither looked to the East, nor to the People (which they were sternly forbidden to do).

This was the origin of the “North-side” position. It is unknown how many clerics of this time took this position. What is known is that all the cathedrals, the chapels royal, and the collegiate churches kept their altar tables unmoved from their chancels, and the priests as in the above images — standing at the wide edge and facing East.

The Laudian Reform

As the Elizabethan era progressed, the Puritan virulence against established practices only intensified, with open rejection of the Liturgy, the Vestments, penance, prayers for the faithful departed, the signs of the cross, etc. As we’ve seen above, they exploited a rubric’s ambiguity to reject worship toward the East. Their numbers kept not diminishing into the Reign of James I. Divisions and scandals were not ceasing.

At accession of King Charles I, Archbishop Laud was commissioned to clean up the mess, and return to the unity which the Church had at the Reformation of the 1540s.

Laud saw that many of the issues stemmed from that initial ambiguous instruction for moving the altar table, which led to so many unforeseen confusions and troubles. Consequently the solution was simple: undo this one instruction, and everything else will settle of its own accord.

This he and other bishops proceeded to do with great energy:

-altar tables of every church (not just the cathedrals, etc) were instructed to be kept in the chancel, even during Communion.

-where altar rails guarding the Holy Table were displaced, they had to be restored.

Much violence and murder ensued by Laud’s opponents due to his reforms, vindicating his judgment that these people could not be allowed in the Church. See the bloody English Civil War, and the heinous executions of Laud himself, and of Charles I. Suffice it to say that all the reverent uniformity one sees in today’s traditional Anglicanism is owed to Laud and other stout bishops of the time. Bishop John Davenant was more vigorous than most, mandating East wall attached Altar Tables from all his priests, and protected by decent and comely altar rails everywhere throughout his Diocese.

The reform which Laud and the Caroline Bishops undertook was not unique to them. Many Reformational groups preserved and valued traditional forms of worship even into the 1600s. Here is the coronation of the Calvinist (not Lutheran) King of Bohemia in 1618:

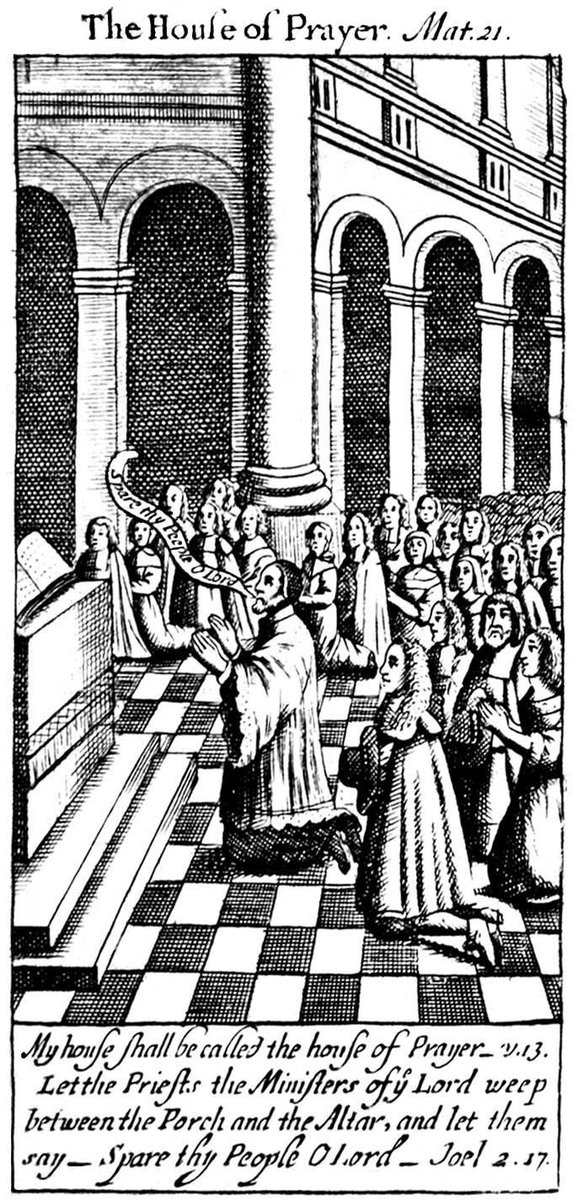

As the 1650s wore on, Archbishop Laud beheaded and the Puritans in charge, the old church seemed to be lost forever. Anglican divines began the slow, patient process of teaching the basics of traditional Christianity all over again. Edward Sparke, “Scintillula Altaris” (1652)

Thomas Comber, “Companion to the Altar” (1676)

Anthony Sparrow, “Rationale upon Common Prayer” (1684)

-one of the most famous commentaries on the BCP

-uses an improved version of Sparke’s 1652 image as a frontispiece for his whole book

-at length describes ad orientem as normative in the Church of England:anglican.net/works/anthony-…

Another engraving, from the 1700s:

Another version looked like this.

(If you have a hi-res version, please contact us!)

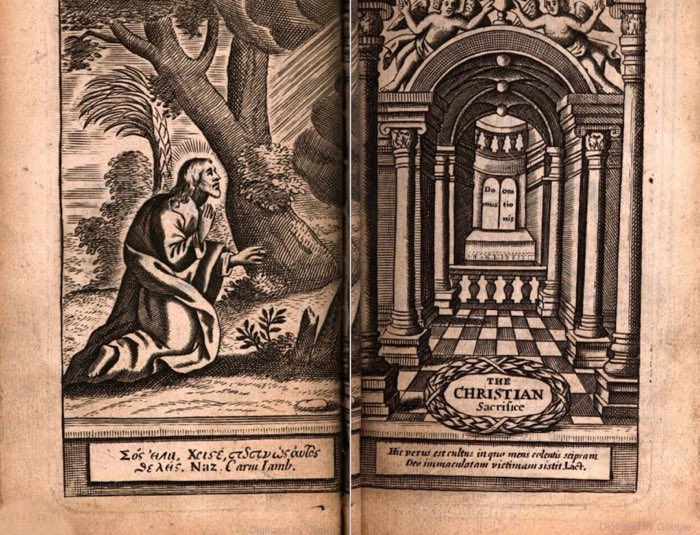

Many other Images depict an ‘implied’ ad ad orientem. In the left image, there is simply no room for standing at the sides of the altar table. In the right image, the altar setting is squarely oriented Eastward (and little room on the sides!)

By contrast, there’s only one well-known depiction of the

“North-side” position:

-church priest stands in place of the heavenly Priest

-heavenly priest faces his altar on its wide East end

-clear contrast w/ where Liturgy Books are shown in other images

britishmuseum.org/collection/obj…

Compare this to the depiction of Holy Communion at St. Paul’s Cathedral from 1736, which is entirely frontal:

• • •