Worship the Lord in the Beauty of Holiness - Benjamin Phillips

Multiple blog pages combined into one, from : https://benjaminphillipsblog.blogspot.com

1. Introduction and the Laudian Movement

It is clear that the success of the Alternative Service Book as a popularised liturgy lay squarely in its revised Eucharist forms. The legacy of the Oxford movement[1]on the wider Anglican Communion had left its liturgical mark, as the changing nature of liturgical practice shifted the “Principle Service”[2] from Morning Prayer to the celebration of Holy Communion – subtitled in the 1980 book “also called The Eucharist”,[3] the first time it had been titled as such in a definitive rite of the Church of England. Unlike in the Daily Offices or the Ordinal, the Church of England's Liturgical Commission inherited a great deal of exploratory and scholarly work on the Eucharist in the post-war period. For liturgical scholars, the major work is that of Dom Gregory Dix, whose The Shape of the Liturgy had influenced every major revision of Anglican liturgical practice since its publication in 1945. In it, Dix had concluded that the Eucharist did not hinge on the words of institution[4] as had previously been received in tradition, but led him to formulate the “four action shape of the Liturgy: Offertory, Consecration, Fraction, Communion.” The work of the Roman Catholic Church in producing its Novus Ordo or “Pauline Mass” in 1970 greatly supported those within Anglicanism in revising their Eucharistic rites.

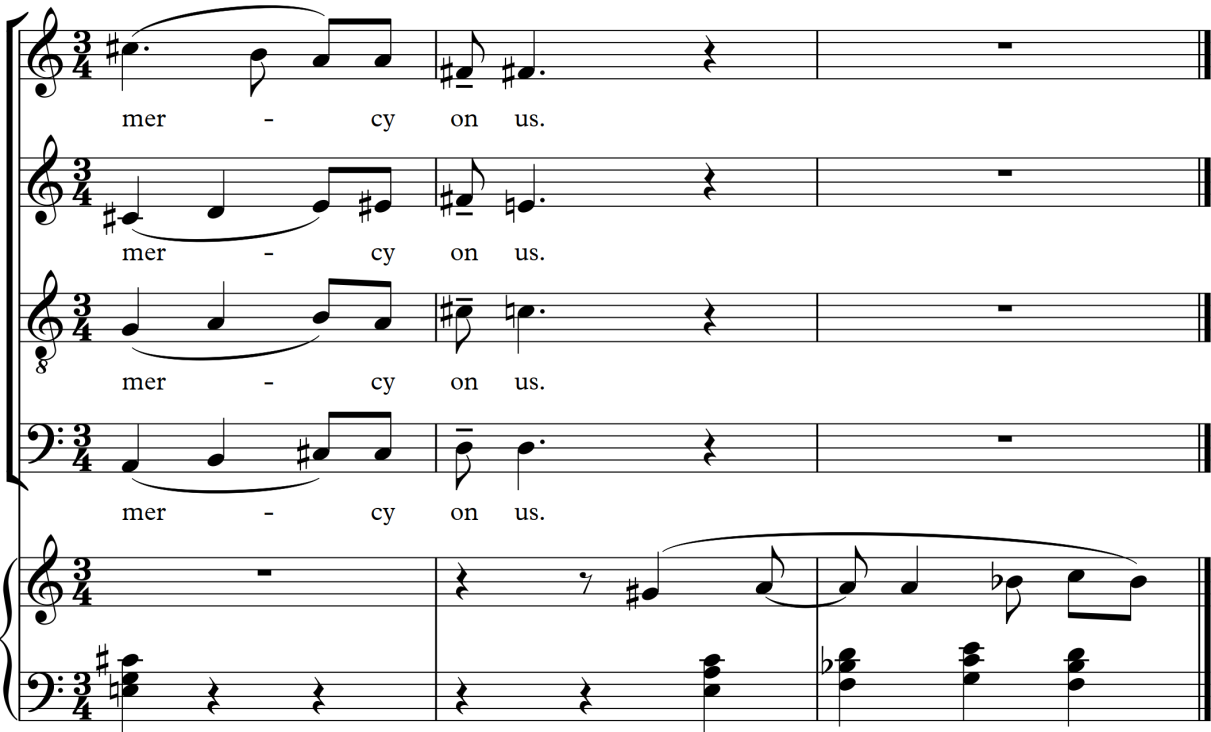

Through the preceding quarter century, the Eucharist had become increasingly the central liturgy of a great many parishes.[5] Whether this was following the Parish Communion movement, or the rarer group who were celebrating the Tridentine Mass,[6] the 1662 Book of Common Prayer was neither supportive of the inclusion of laity,[7] or flexible for those who wished to enrich it from other sources.[8] Musically, the 1662 Communion was a sparse affair – those who stuck to the printed service would experience the following:

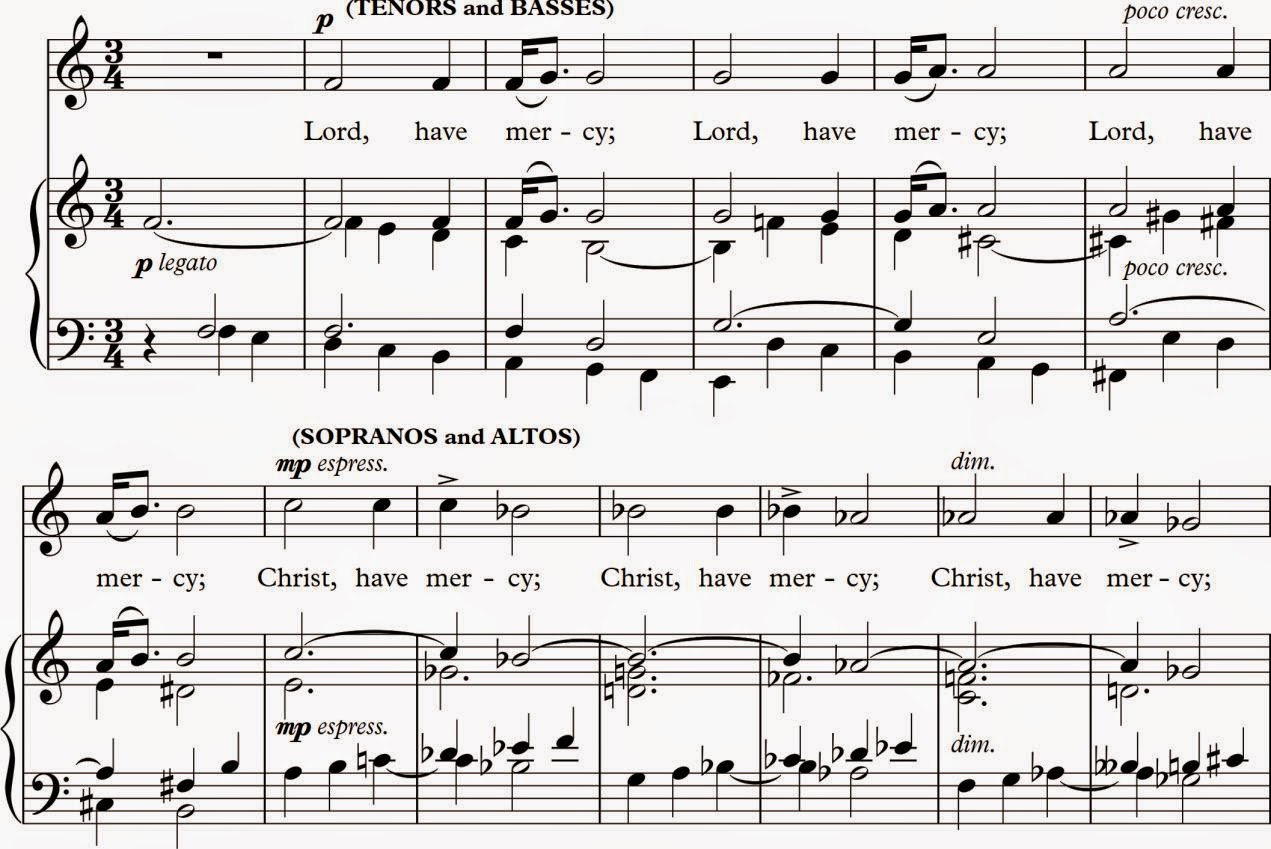

Responses to the Ten Commandments Each of the ten commandments would be read, followed by the phrase 'Lord, have mercy upon us, and incline our hearts to keep this law'.[^9] After the tenth commandment would be said 'Lord, have mercy upon us, and write all these thy laws in our hearts, we beseech thee.'[9]

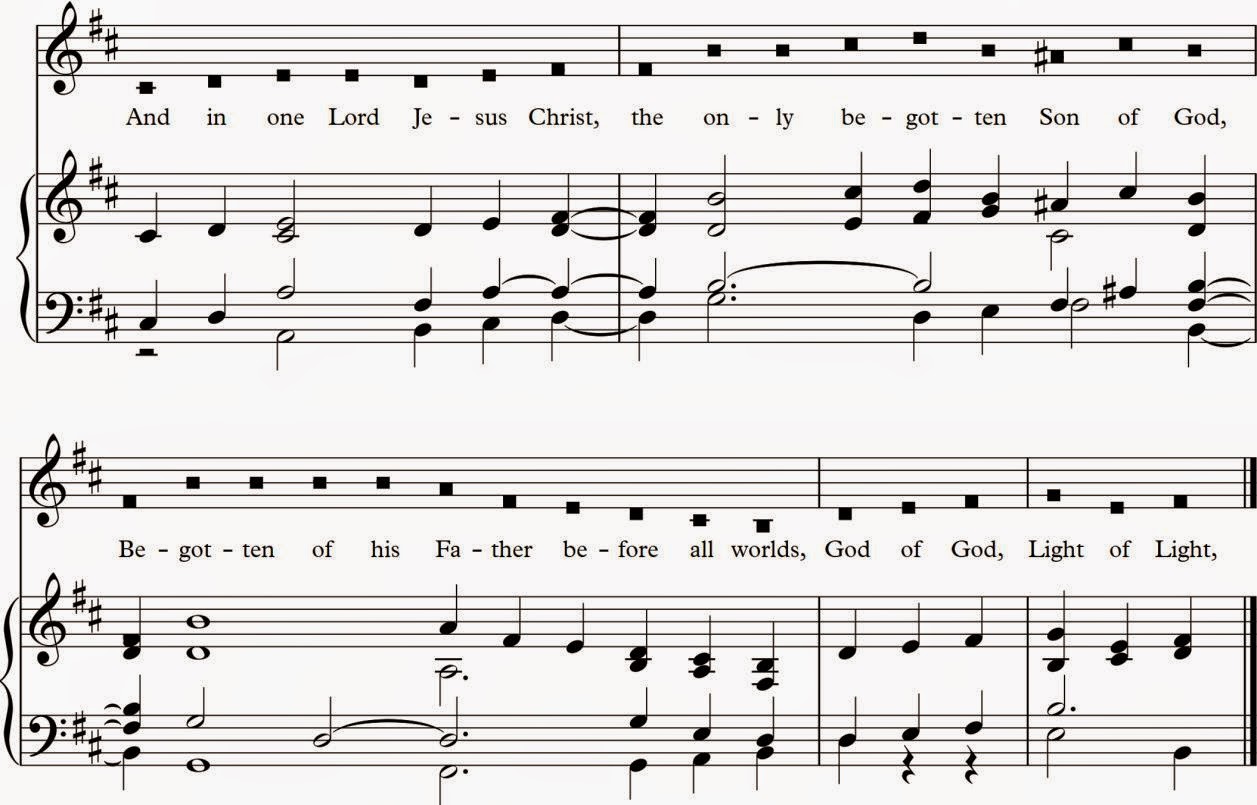

The Creed The Nicene Creed, an article of faith agreed at the Second Ecumenical Council of 381AD, recited at the Eucharist since that time, and continued in the Church of England following the reformation.

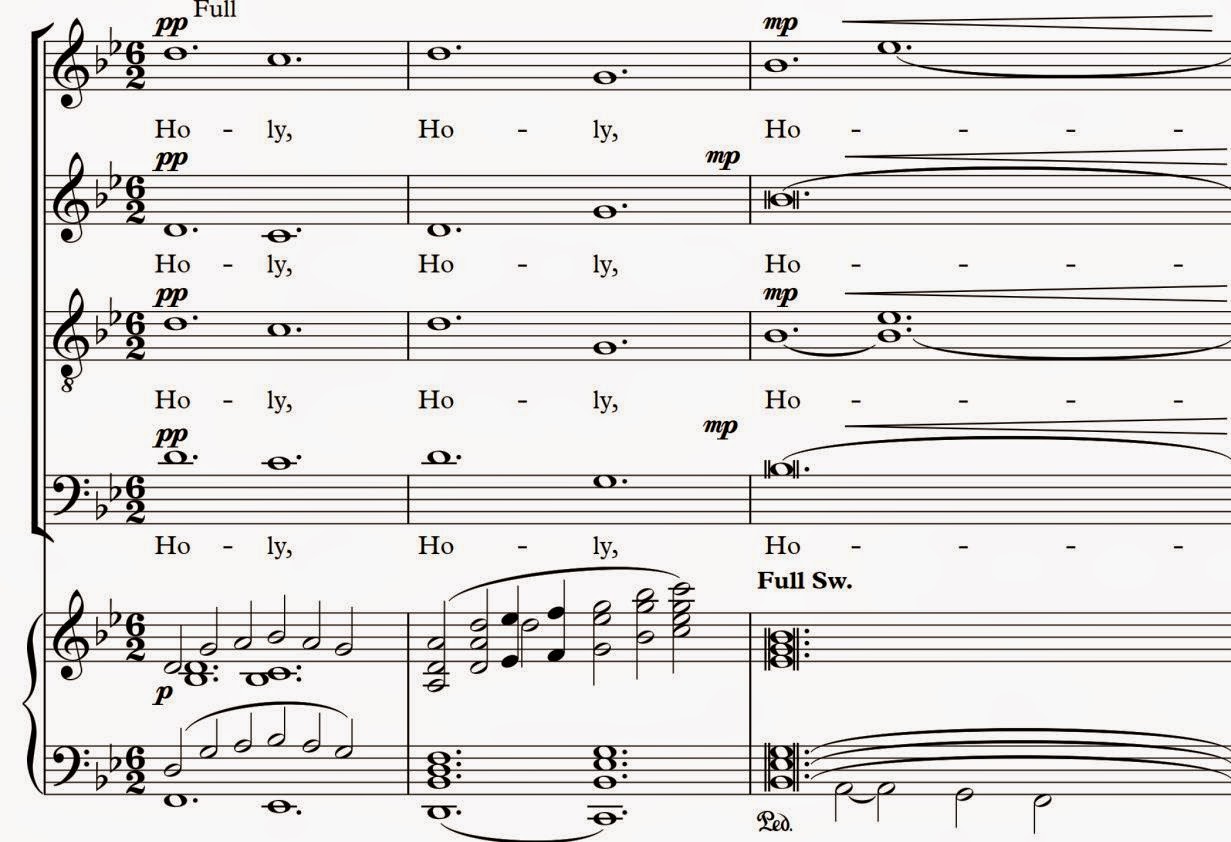

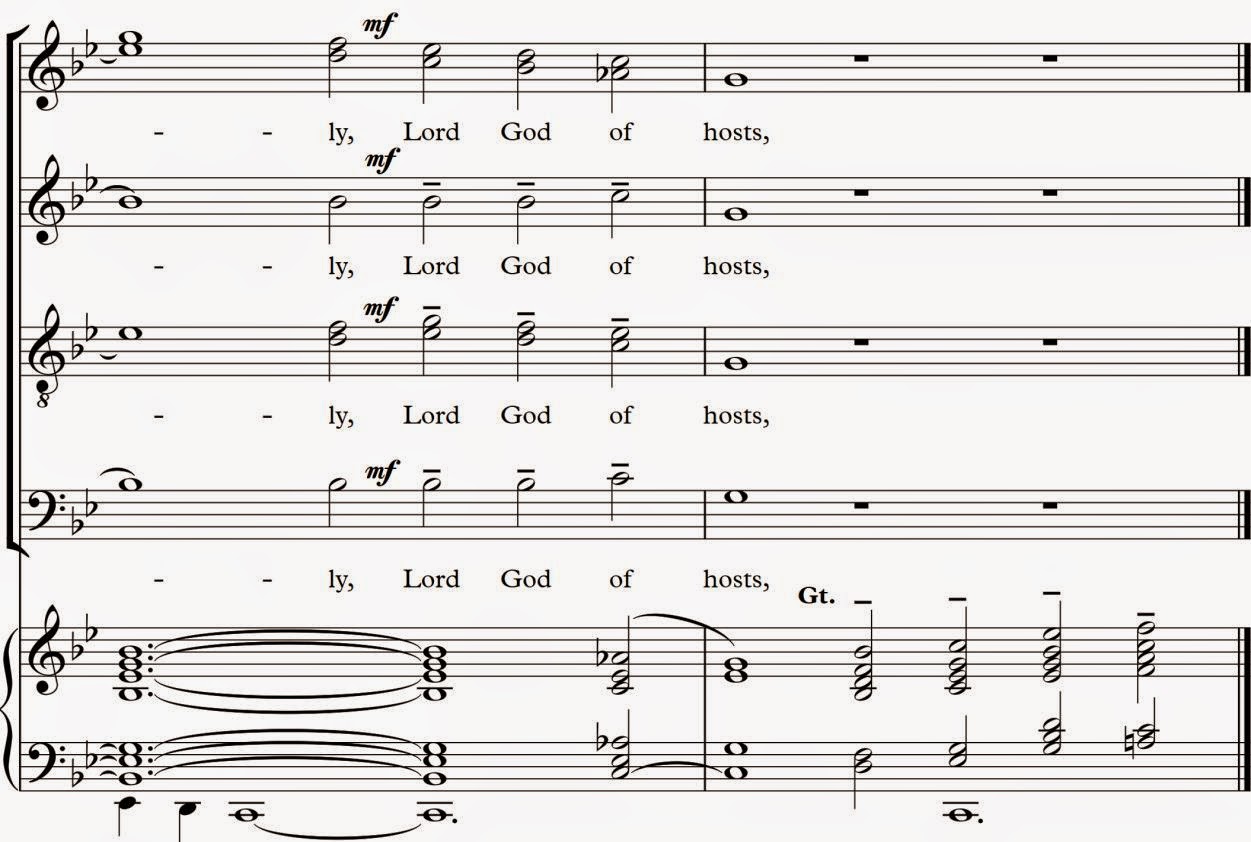

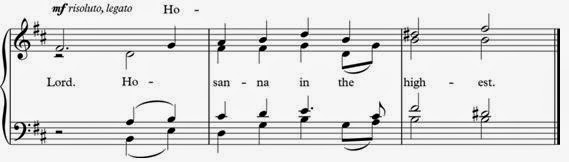

Sanctus Part of the Eucharistic Canon, the texts relates back to Isaiah 6:3, as a song of praise to God.

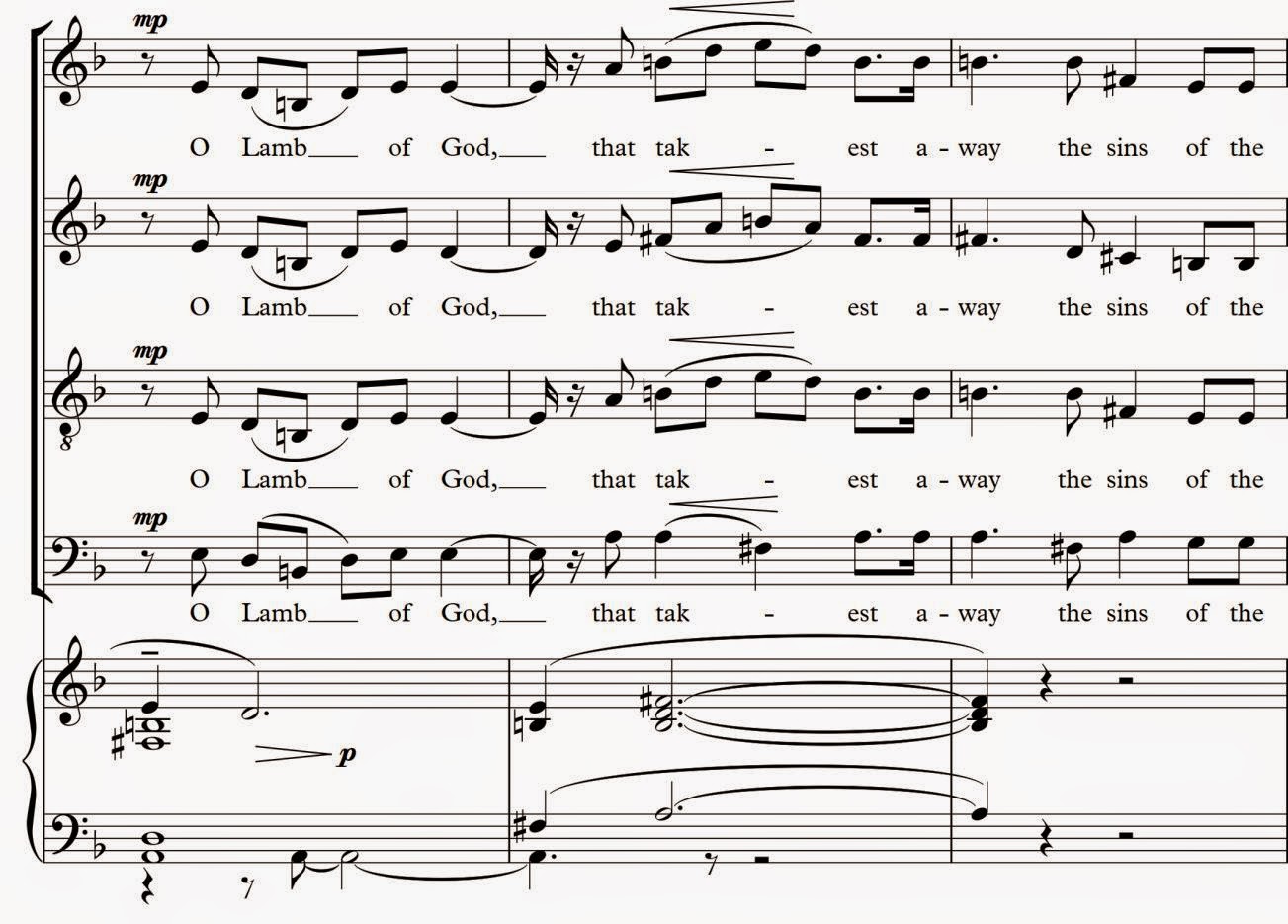

Gloria in excelsis A fourth century hymn of the church, relating our thanks and praise to God. Inspired by the apparition to the shepherds in Luke 2, it continues giving thanks whilst interceding for mercy.

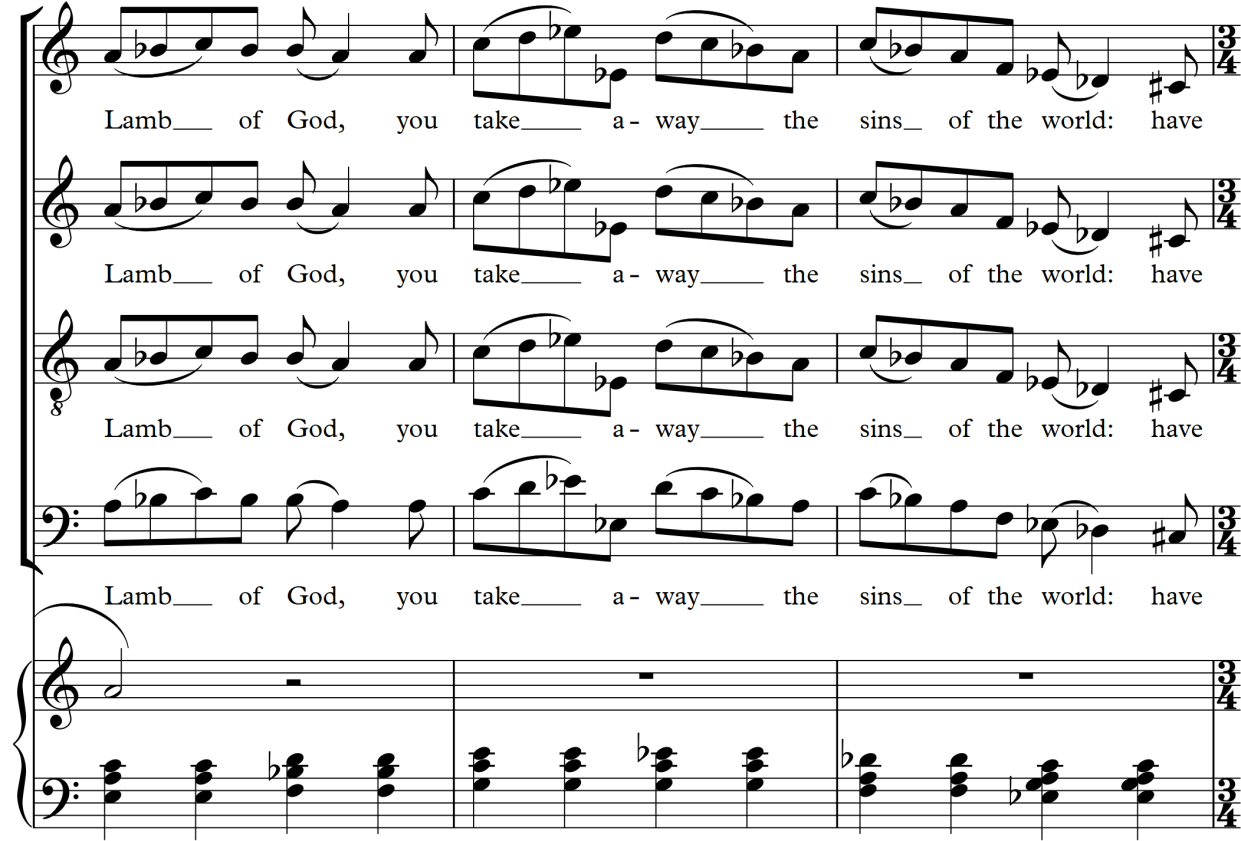

Controversies during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries included whether or not the inclusion of the antiphon Agnus Dei and the re-joining of Benedictus qui venit to the Sanctus were legal, right or suitable within the Church of England.[10] These texts were certainly identified as belonging to the catholic wing at the turn of the century, as is evident in the omission of them from any original Stanford communion setting written in English.[11] John Ireland, whose leanings were Anglo-Catholic, included the Benedictus and Agnus Dei in his service in C, written in the fin de siècle period.[12] Growing need for music suitable for the laity to join in singing started to become a factor during this period – the re-emergence of John Merbecke's Booke of Common Prayere noted[13] provided many able congregations the possibility of being able to sing the Eucharistic texts. Those who worshipped in churches which were more “roman” would have found themselves using the Plainsong and Mediaeval Society's The Plainsong for the Holy Communion, singing the 1662 text to the plainsong found in the Graduale Romanum. The publication of the English Hymnal in 1906 saw the translation of the assorted introits, graduals, tracts and sentences for use at the celebration of the Eucharist from the Graduale into English, commencing a welcome musical enrichment of the Eucharist in the English language. Many original compositions for parishes and cathedrals were composed during the period between 1900 and 1965; many could be described as adequate for parochial use such as Martin How's Anglican Folk Mass,

some were settings which would be acceptably sung by any good parish choir of the period, or any Cathedral choir, such as Harold Darke in F,

or an ethereal composition such as Herbert Howells' Communion service Collegium Regale, written for King's College, Cambridge in 1956.

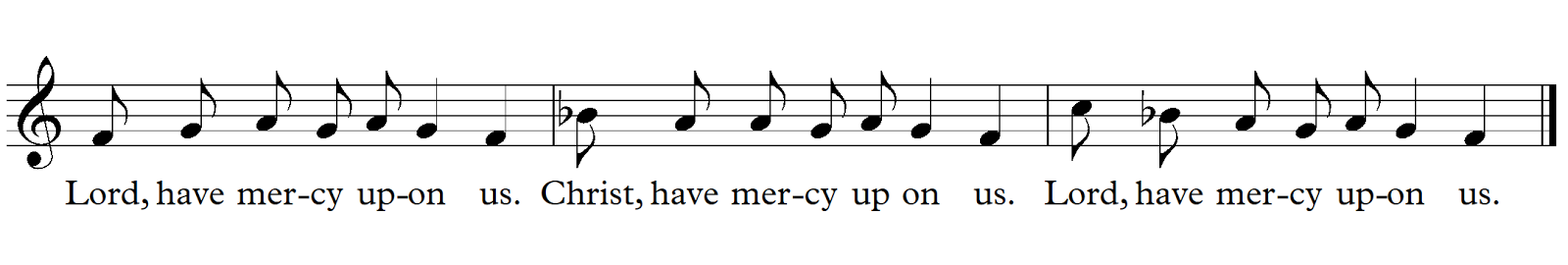

At this juncture, one should mention the work of Father Geoffrey Beaumont and the “Twentieth Century Light Music Group”, whose efforts, whilst short-lived, did have a small lasting effect. Beaumont's own composition A Folk Mass was something of a liturgical wonder for several years, before, like many liturgical fads, succumbing to a wane in popularity. The lasting effect of this group was to introduce hymnody that was both accessible and easily understandable to the current generation, without carrying a pomposity that Victorian and Edwardian writers encouraged. Patrick Appleford's tune Living Lord, coupled with Beaumont's words Lord Jesus Christ, you have come to us makes clear the purpose of the Eucharist in direct and easily understood language, whilst having a tune that is lyrical yet not requiring great skill musically. The example below demonstrates the competency needed in order to produce it satisfactorily,

The change in Eucharistic liturgy that led to those published in the Alternative Service Book brought with it a whole new way of “doing Eucharist”.[14] The idea that, amidst the changes in language and ritual, musicians and music would remain the same as before was unthinkable. However, unlike in the Daily Offices, because a great deal of experimental work had been done (both officially and unofficially) for nearly a century before, the ground been prepared for revision, and necessary work had been done, by liturgists and musicians in preparation.

Whilst, the idea of full dialogue (both spoken and musical) between priest and people was refreshing in some places, and re-enforcing what had become the norm in most, there were casualties of this era. For those singing in parish churches, the advent of this era brought with it the sad, if inevitable truth that whilst inclusiveness and modernity bring the church further into the twentieth century, and, at least for a time, would make the emerging 'Anglican' identity[15] popular, it would weaken and eventually destroy the parish choir tradition. Not for one moment was this intended: however, it was unavoidable. The novel idea of a choir “leading”[16] the congregation (as envisaged by the Cambridge Camden Society[17] in an age where people were literate and more culturally educated was unacceptable in the modern church. The new concept of liturgy was that it was “done with” not “done for” the laity. Eastward facing celebration[18] and cleric-domination[19] of the liturgy gave way to the altar being put in the midst of the people,[20] and greater lay involvement.[21] Gone were the days of the choir being enthroned between altar and people – at least, in liturgical thought of the period. In many parishes, the role of the choir was put under intense scrutiny. Clergy trained in theological colleges where music was not a key part of curriculum or common life[22] began to see choirs as exclusive, when the liturgy[23] and, in their mind, the wider church was mutually inclusionist, leading to issues, dismissals and a great deal of hurt and schism. Where clergy and musicians worked well however, and worked together to acknowledge their new found situation, music flourished – albeit not in the way it once had.

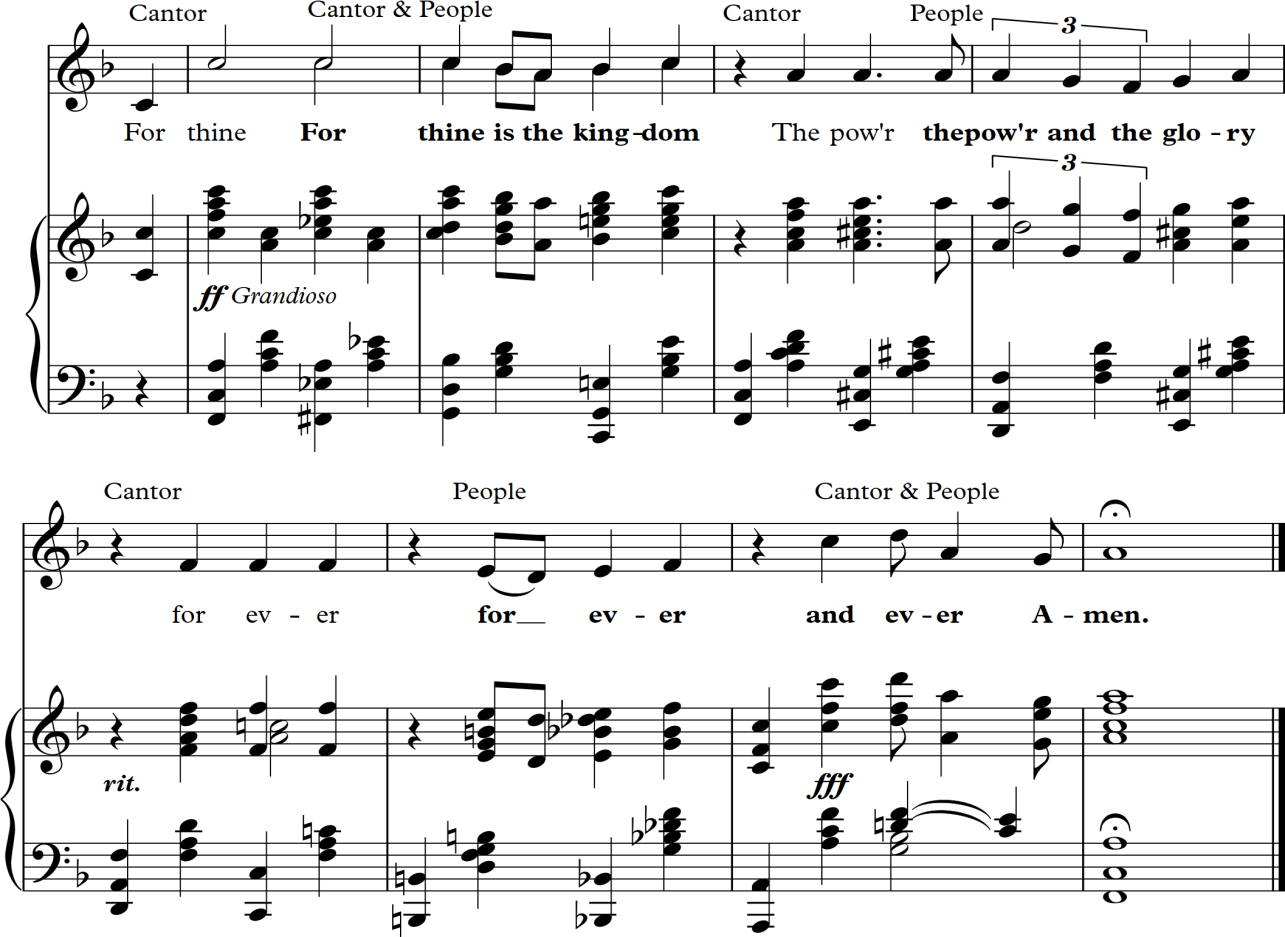

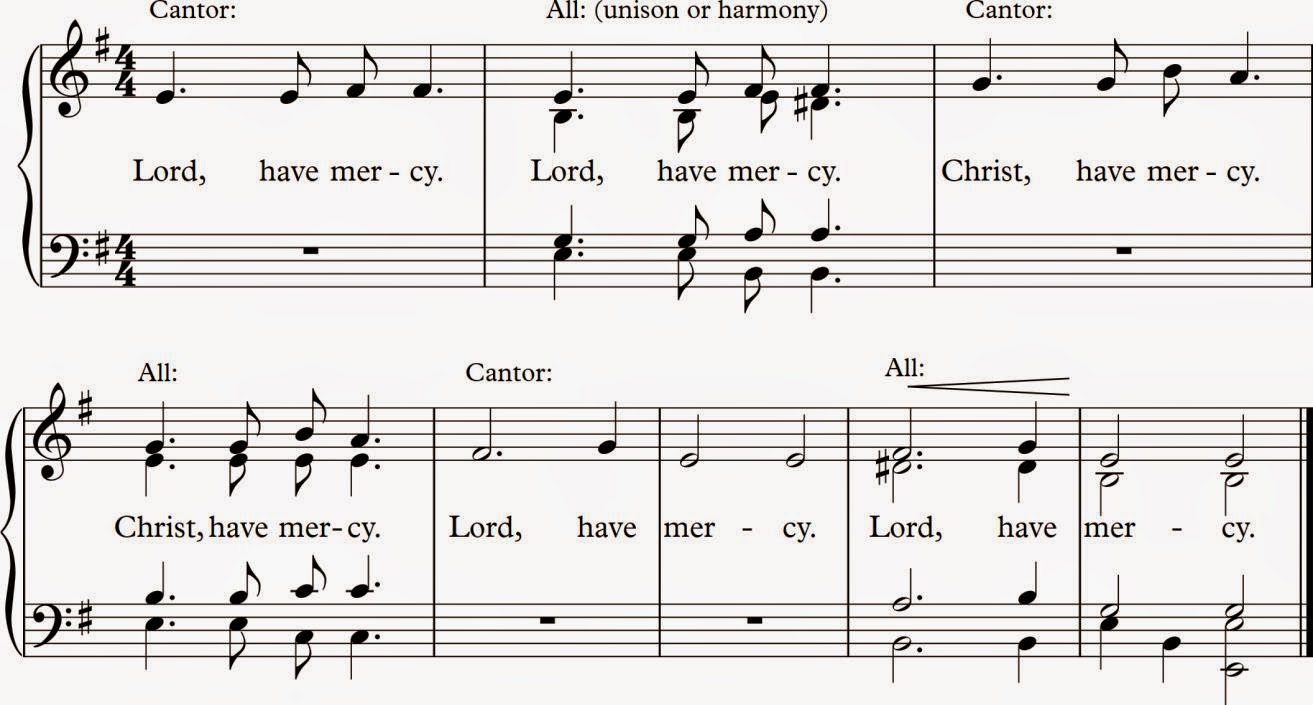

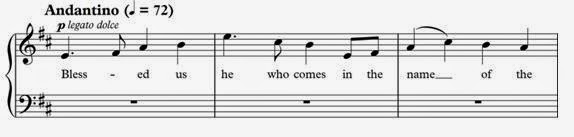

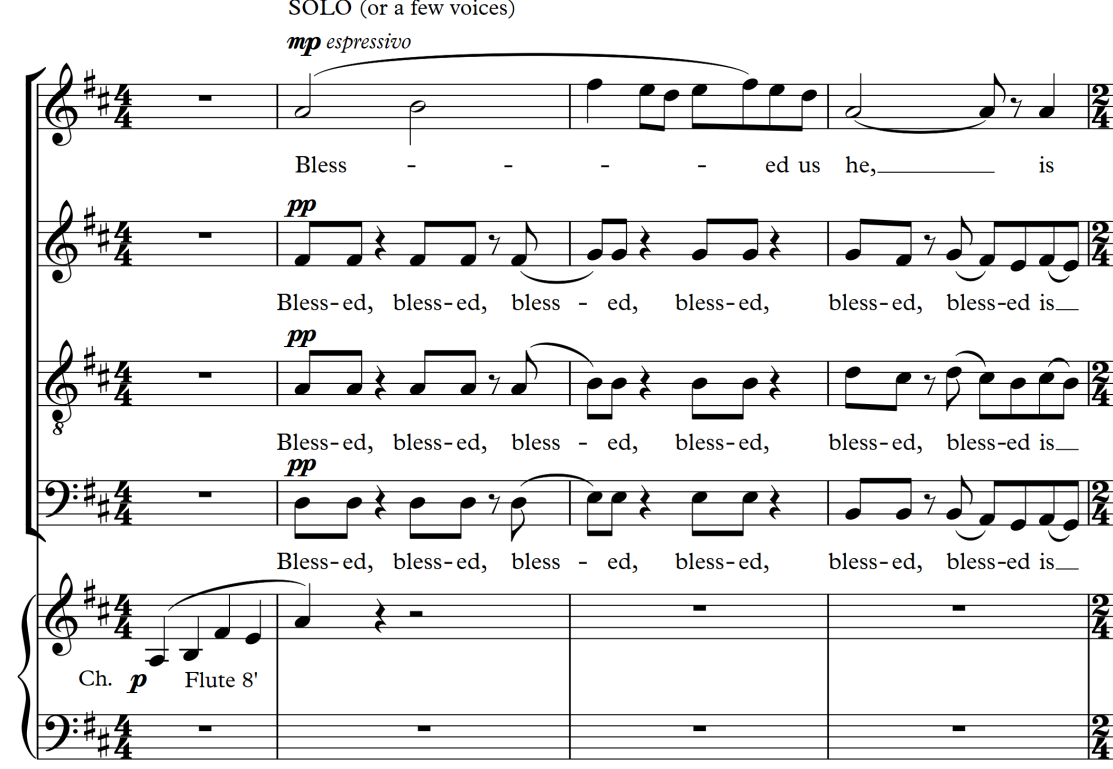

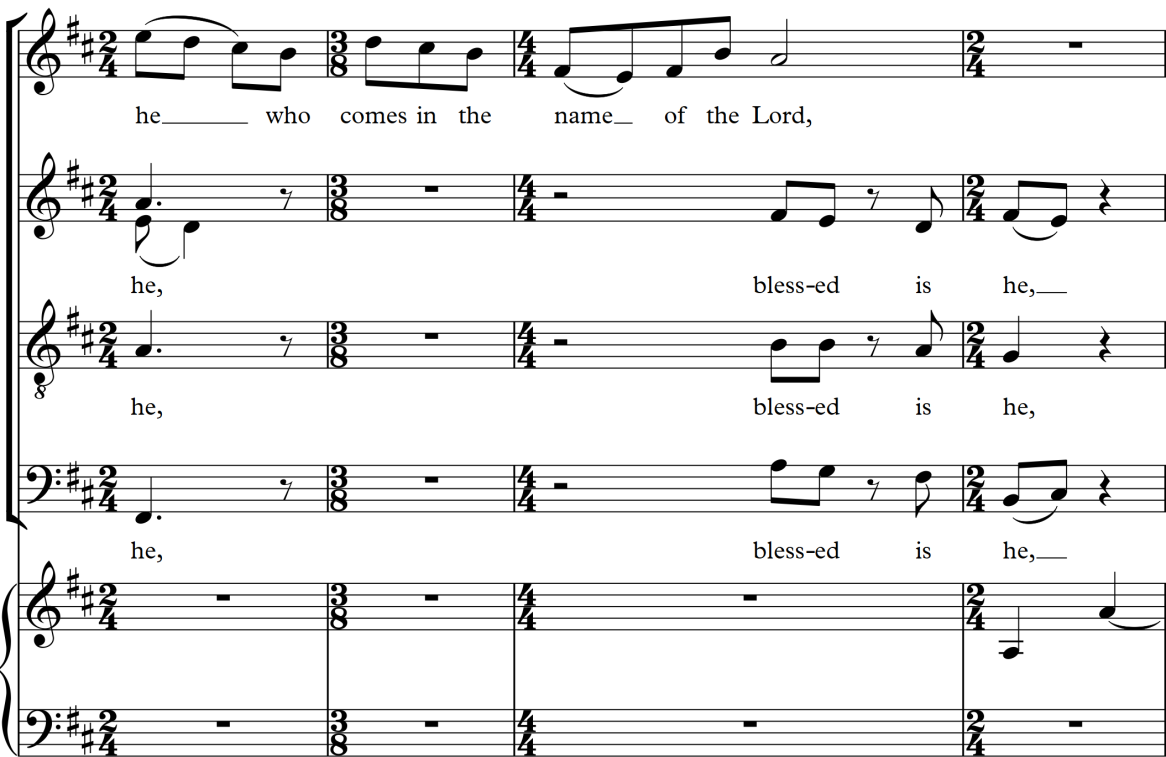

The Communion Setting by John Rutter, privately commissioned by members of the Liturgical Commission, and published in 1972, demonstrates that whilst the compositional style that subjugated the parish music movement had been either trying (often unsuccessfully) to imitate cathedrals and those parishes which had greater musical resource, or were reminiscent of non-conformist “Sanky[24]”-style effected harmonies. Whilst written with the dominance of a congregational melody, Rutter writes in the score “Suggestions for disposition of voices…are optional and apply only to the choir”.[25]

We see that, whilst being accessible to congregations as a setting, Rutter (and many composers writing around this time) still envisaged that some leadership would be exerted by a group of singers which would be separate from the congregation.

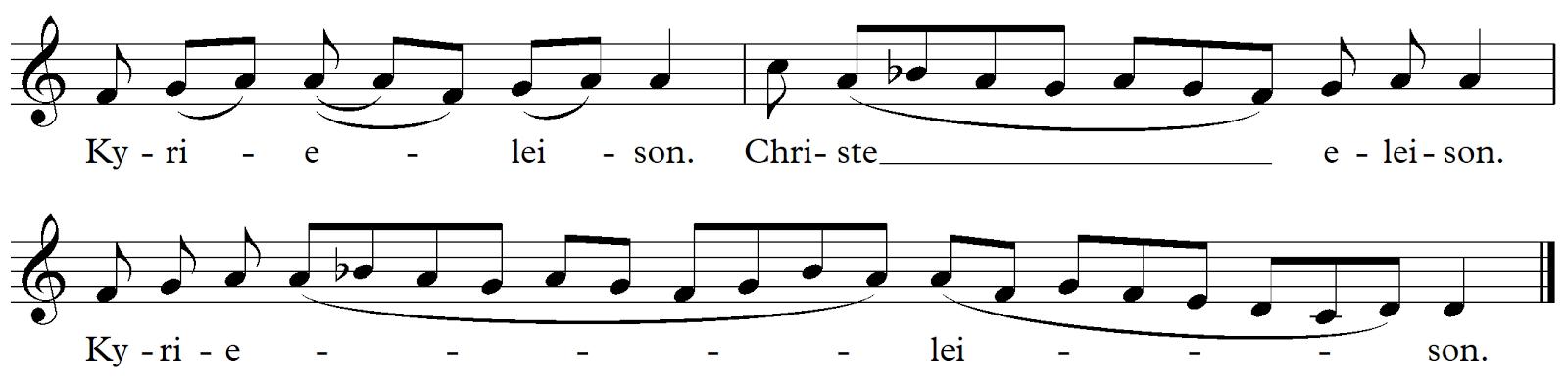

However, a growing movement being embraced by parishes where either a choir had disbanded, encouraged by those influenced by the Novus Ordo of the Roman church, was replacing the choir with a cantor, encouraging repetition and call-and-response. This idea had been seen in Geoffrey Beaumont's work (as illustrated above), but one of his students at Mirfield, Patrick Appleford, utilises this well in his New English Mass, published in 1973. The Kyrie, a simple call and response, works well even in places where musical talent is at a low ebb.

Whilst parish churches experienced both liturgical renewal and a changing role for their musicians, in cathedrals and greater churches[26] the breadth of variance that the new Eucharistic rites offered would greatly enhance their musical programmes. Before that time, it was rare to hear the masses of Haydn, Mozart or Schubert sung liturgically. Some of this was to do with the variances between the order of Eucharistic canticles between the Roman Canon and the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, but there was still some perceived views regarding the use of Latin within an “English” service. Whilst plenty of Anglo-Catholic bastions[27] employed orchestras occasionally for these masses to be performed, the further away from the South-East of England you got, the concern there was regarding the use of Latin. This was, fortunately, swept away reasonably quickly, as the arguments against the use of Latin could almost be used by extreme modernists arguing against the use of the 1662 texts at a Rite A[28] Eucharist. It was clear, however, that the sung portions of the Eucharistic liturgy would need setting, and this began to take place rather quickly. Two settings, commissioned by Allan Wicks and the Choir of Canterbury Cathedral demonstrate the changing musical face of liturgy in this period. Anthony Piccolo's Canterbury Mass, written for the Petertide ordination service in 1978, whilst the Cathedral's organ was being rebuilt, encapsulates certain features which aid the composition's total length of four minutes. As a totally unaccompanied piece, there is no need to add length with introductions or elongated part writing: it is direct and to the point. The Sanctus and Benedictus length of twenty bars shows that Piccolo has taken note of Wick's alleged complaint about the length of the Ordination liturgy, and has worked to keep the entirety of the setting as succinct as possible whilst expressing the solemnity of the text in a way which does not devalue it.[29]

Barry Fergurson, Organist of Rochester Cathedral during this period, received a commission from Allan Wicks for a Eucharist setting for Christmas Morning, 1985.[30] The Kent Service[31] demonstrates the compositional genre of the Organist/Composer well, and Fergurson's composition is sadly a gem overlooked by many today. Fergurson's style plainly sets it within the Cathedral repertoire, exploring the use of verse and antiphony, harmonic language which for Anglican repertory of the time was modern, with more than a passing nod both to the English and French church music traditions. The inclusion of Gospel Acclamations, Eucharistic acclamations, a doxology to the First Eucharistic Prayer and a dismissal demonstrated that it was looking forward in language, but also hearkening back to the settings of John Ireland, Harold Darke and Herbert Howells, who also wrote in their settings for other parts of the Eucharist.[32] The “idea” of Cathedral worship at this time was that the clergy and choir offered it on behalf of the attending congregation.[33] This setting certainly continues that tradition, but encapsulates it in excitement and dissonance which would have been certainly novel to many attending that Eucharist on Christmas Morning 1985.

It is clear that the Eucharist was able to cater, in a liturgical and musical sense, to a wide demographic within the church. Whether you felt ideologically attracted to a catholic Novus Ordo inspired worship, preferred the grandeur and non-participatory nature of cathedral worship, or experiencing a non-communicating mass celebrated in the manner of the Tridentine liturgy,[34] there was a way to express this within the confines of the Alternative Service Book's parameters. Musically, it gave a safe re-entry to the repertoire of many cathedrals to the masses of William Byrd, along with those of Palestrina and Victoria. Finally, the full texts of the Schubert, Haydn and Mozart masses could be performed liturgically in Latin, without the butchery of excluding those texts omitted in the 1662 Eucharist. The long-standing ideas of congregational participation forwarded by those on the catholic wing of the church, particularly Beaumont, Appleford and a whole generation of clergy trained at the College of the Resurrection, Mirfield, grew to new levels, seeing an outpouring of congregational settings by composers including William Mathais, Grayston Ives and Richard Shephard.

The life of the Alternative Service Book was short. Its original life-span, a mere decade, was doubled, as the Liturgical Commission had not been in a position to commence work on any larger projects at the end of the 1980s. Its lifespan, whilst short compared to many liturgical works, delivered the Church of England into a new age of modernity, where legalised experimentation within the liturgy would not be as controversial, and paved the way for further experimentation within Common Worship. As a working experiment in itself, the Alternative Service Book had strengths and flaws. For musicians working within the church, its main strength was the Eucharist, which allowed them to enrich the repertoire of Stanford and his ilk with the wonders of pre-reformation English, Spanish and Italian schools, as well as those of the French and Austro-Germanic composers of the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The Daily Office provisions sadly were wasted on musicians, and seemed to receive little praise from clergy and congregations either, entrenching an already deep reliance on the 1662 provisions. Further work in Common Worship has moved the Daily Offices further towards its spiritual goal, but it seems that the policy for sung services will remain unchanged, and commissions and publications for the 1662 canticles continue. The Litany within the Ordination rite demonstrates the need for composers to set to music the new texts for practical as well as aesthetic needs. This continues, and with the advent of the seasonal resource Times and Seasons within the Common Worship “family”, the need for greater “one-off” seasonal compositions will grow from places that are liturgically aware. The disappointment of the Alternative Service Book is the lack of interest, and indeed, omission from the Commission, of musicians during the period of its drawing up. Whilst that has been remedied with the appointment of the Royal School of Church Music as “official agency”, who now advise and provide music for inclusion within new publications, the breadth of thought they represent is reasonably narrow. Gone are the days of successful parish church choirs flourishing the length and breadth of the country; instead, music groups, mixed instrumental ensembles, even recorded and electronic music[35] replace the robed choir of men, boys and girls. Cathedral choirs continue mostly in the ascendant – many now beginning to specialise in particular genres of the choral music canon. Much is still written primarily for this medium, with commissions for the more prominent foundations now incorporating modern compositional techniques for voice,[36] as well as for other instruments apart from organ. The church has, to a greater extent, accepted modernisation, whether that is in music or liturgy, without schism or major conflict. It is difficult at the time of writing to wonder what, when the Common Worship brand is concluded, musicians and liturgists will write about the musical contribution it left. But, for the Alternative Service Book, we are in a position to take stock. Directly, the legacy is one which has enabled liturgists, theologians and musicians to take time to work out key precepts before carrying on to another revision – Common Worship. Musically, on the face of it, there was little impact: the Daily Offices continued, where sung, to be offered from the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. There were new texts uniquely in the Alternative Service Book set to music,[37] neither was there much formal support from the central Church for doing so. Its positive legacy is in the Eucharist – not that there was a cascade of settings set to the modern texts, but in that it re-opened such a wealth of repertory ignored by Anglican musicians in a liturgical context for nearly half a millennium, which has greatly nourished the spiritual and liturgical life of the church since its reintroduction.

The Church of England now is at the most liturgically diverse point in its history. The need for music to play a role within worship is recognised as being fundamentally important. The wide-range of musical genres cross traditional boundaries: catholic and evangelical, low and high, embracing both traditional and modern, worship song and excerpts of Handel's Messiah. Without the Alternative Service Book, and the openness that it brought liturgically, then the freedom in rubric and interpretation offered by Common Worship would not be possible, restricting musicians and liturgists greatly, and not being able, like those whose works are cited in this paper, to make worship proclaim the Christian faith '…afresh in each generation.[38]'

2. its background

The area of church life where the impact of 'beauty of holiness' would be most felt was in and through the liturgy – its conduct and administration, but also the aesthetic of the functional objects used, such as vestments, altar-wear and furniture. The tumultuous era between the publishing of the first English prayer book in 1549 and that of the outpouring of the Savoy Conference[39] that produced the revised edition in 1662 demonstrated the factionalism with which the English church was faced. On one side, there was a puritanical neo-protestant group, whose value on worship had moved from collective to the individual expression. Those of a more 'High Church' perspective retained certain beliefs and ideas from prior to the secession from Rome, but at no time could be considered as 'Roman' in any sort of way that some of their successors in the Oxford Movement of the later nineteenth century would.

The puritan forces, like those on the opposing side, represented a cacophony of ideas, beliefs and thought. The noted church historian, G.W.O Addleshaw, comments on its general binding factor:

Protestantism has always been at its weakest in its thought on the Church and finds it hard to rise above thinking of the Church as a collection of individuals. Its idea of liturgy tends to be the meeting together of the godly in prayer, and the using by individuals of one common form.[40]

For the majority of the populous, here was the incredible weakness of the puritan view – a weakness that continued well into the middle of the twentieth century. Whilst the publication of 'one common form' in the succession of books between 1549 and 1662 can be acknowledged as a protestant form, it nevertheless would not have changed the individual churchgoers views on the myriad of beliefs and practices that they would have either been brought up with or learnt from others during their formative years. John Harper, in reviewing the Communion service of 1552 (which veered further towards the neo-protestant and puritanical position), concludes that

The majority [of people] accepted the real presence of Christ in the consecrated bread and wine. However, the vocal and influential Puritan faction (close in outlook to the Genevan Church) regarded the liturgy as a memorial meal, the Lord's Supper, rather than as a sacrament of Holy Communion. For them there was no question of real presence: this was a shared holy meal, remembering the Last Supper ('Do this in remembrance of me').[41]

From its earliest times, the Church of England was in effect trying to accommodate divergent views on the nature of the sacrament of the Eucharist,[42] one which continues to create tension today.

In order to understand the Laudian view of Eucharistic celebration, we must look back to the 1549 Prayer Book – the first prayer book of Edward VI. It seems that liturgical change was backed by those who acted as the young Sovereign's Regency Council, headed by John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland, but it is now recognised that Edward himself played a great part in religious affairs, being guided by Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury. Much of the liturgy of the Chapel Royal was still being conducted in Latin – it is certainly understood that Henry VIII continued worship we would understand as being nearly indistinguishable to that of Catholics at the time. This Latin worship needed to be converted into English – for political, theological and ecclesial reasons. It is certainly for this reason that Dudley and his fellow councilmembers issued instructions for the Epistle and Gospel to be proclaimed in English following the accession of Edward VI, leading to the need for greater liturgical resource in English. Cranmer's own English language Eucharist of 1548, which was combined with other material to from the 1549 Prayer Book, draws mainly on the Sarum Missal (as revised in 1542, and most likely was the use of the Chapel Royal) as inspiration, along with parts from the reformed breviary commissioned by Pope Paul III of Francisco, Cardinal Quiñones of 1535,[43] and the Simplex ac pia deliberatio of Hermann von Wied, Archbishop of Cologne of 1543.[44] It is clear now that in structure and (for the most part) in text and ritual, the 1549 Eucharist was greatly influenced by the Sarum Missal of 1542. The Booke of Common Prayere noted by John Merbecke, published in 1550 provided musical material for the new prayer book – indeed, it included the tones (written in plainchant) for not only congregational responses or what we would now term as part of the Ordinary,[45] but also the tones for the consecration, chant for the offertory and post-communion sentences as well as tones for the Sursum Coda, the Lord's Prayer and the pax – much of which would be swept away in the second revision two years later.

The 1552 Prayer Book gave greater ground to those of the neo-protestant wing which can be demonstrated in the change of position of the Prayer of Humble Access (“We do not presume to come to thy table…) the introduction of the Ten Commandments, replacing the recitation (or indeed the singing) of the Kyrie Eleison; the placing of Gloria in Excelsis at the end of the Communion rite rather than following the Kyrie Eleison; In its radical departure from the 1549 Mass, the 1552 Holy Communion service destroyed any concept of real presence, of celebrating and offering the sacrifice of Christ for the living and the dead, and of sanctifying the elements by omitting words such as celebrate, bless and sanctify. Instead the emphasis was on memory, to recall in narrative the death of Christ as shown by the destruction of the unity of the prayer of the people with the consecration and prayer of oblation, which in effect, significantly changed the liturgy from one which was catholic to one that was protestant.[48] No longer was the celebration to be offered at the altar but at a table placed either 'in the body of the churche or in the chauncell' with the priest standing at its northern end. The removal of the manual acts[49] again symbolises the puritanical turn that the 1552 book had taken. That, by 1559, a compromise was achieved on a great deal of these changes – reintroduction of certain manual acts[50] into the 1552 prayer of consecration, a temporary reprieve for Latin-rite vestments,[51] however the use of the cope was encouraged by the priest-celebrant,[52] as well as the return of certain 1549 texts for the distribution of the sacrament. It is because of these larger differences and, until the 1661 Savoy Conference, lack of formal agreement, that the Laudian experiment could take place. I use the word 'experiment' advisedly – for we do not see a full recounting of the Sarum model of liturgical practice, but neither do we see its practice wholly eschewed. It seems to be an acceptance of some key ideals, whilst remaining true to the characteristics of the Henrician break with the See of Rome.

3. The celebration of the Eucharist according to the Laudian Movement: an introduction

Beauty of Holiness enacted – the celebration of the Eucharist, according to the Laudian movement

In order to understand the movement, we must look at the focus of their efforts in action. We have little pictorial evidence of Laudian worship in action – one of the myriad of reasons for the lack of a multitude of engravings and paintings would be a political one, as within the Church's own politik, seeing senior dignitaries[53] performing the rite in a way that would cause consternation, resentment and division would be, and eventually did become a catastrophe for the Church of England. When we look at the liturgy as they conceive it, we see that it is not uniform within the movement. There are wide spread deviances within the movement, depending upon which branch of the movement is followed. The evidence available suggests that, for the most part, Laudian principals were fully enacted in places where a) there was generally a 'common mind' in following it (such as Cosin et al. in Durham,[54] and later at Peterhouse), or b) in a private oratory or chapel where there was dominance by its Ordinary.[55]

The following photographs are intended to demonstrate the 'common use'[56] of Laudians celebrating the sacrament of the Lord's Supper, in a manner that is as authentic as one can be given the timeframe for the preparation of this work. For the most part, I have sourced the staging for these movements from accounts given of the practice of Bishop Lancelot Andrewes in his private chapel and other liturgies in which he was involved, cross-referencing with works done on this by the late Kenneth Stevenson,[57] a paper given by Mariane Doorman at the 1999 Westminster College conference on Reformation Studies[58] along with a more general overview given by G.W.O Addleshaw in his work The High Church Tradition.[59] Where no evidence is sufficiently available, I have attempted to interpret the 1559 rubric in the spirit of the Laudians whilst remaining reasonably faithful to the text of the rubric.[60] The location for these photographs, St Davids Cathedral in Pembrokeshire, is fitting, as this was William Laud's first episcopal See in 1621. Holding two ecclesiastical offices, it is unlikely he would have visited his cathedral much,[61] but, as will be demonstrated in these photographs, both the architectural and liturgical legacy of Laudianism has played a great part in shaping the worshipping life of this and many other buildings.

If the accounts given of a Laudian celebration are to be believed, their liturgy would resemble something deeply mystical, full of ritual yet very English and reserved. For us, in the twenty-first century, there are many aspects of the celebration that have unchanged, so the thought of controversies over basic vesture and the type of 'bread'[62] seem almost unimaginable. The use of incense, of the mixing of the chalice[63] and eastward facing celebration indeed did cause issue again during the rise of the Tractarians, requiring legal and constitutional safeguards, and can indeed still raise an eyebrow in some churches today. At the entry of the ministers, we see them in order of their role within the liturgy – at the front is the clerk or Sub-deacon,[64] followed by another clerk or minister (the deacon), followed by the priest-celebrant. The differentiation would be in vesture – the three ministers here wear copes, which are of a similar shape and design to those which would have been worn during the Laudian period, over their surplice, scarf, preaching bands and hood..[^13] This certainly enforces the increased sacerdortalism that the Laudian movement encouraged.

4. The celebration of the Eucharist according to the Laudian Movement part 1

The arrival at the altar would be marked by the ministers forming in front of it to reverence it – the assisting ministers would bow, whilst the priest would kiss it. We have evidence to suggest that at this point in Durham, there would be an Introit rather than a metrical psalm favoured by the neo-protestants.[65] Whilst it is possible that seasonal sentences of scripture[66] were used, there is a case to look at the musical settings of collects[67] as serving this purpose. Peter Webster, in his dissertation on the relationship between religious thought and the theory and practice of church music in England which looks exclusively at the Laudian period, suggests that these collects were set to music suggesting 'a [Laudian] “desire to express the hierarchical structure of the church year in polyphonic music”, a desire peculiar to the new 'Laudian' style.'[68] The use of these as an introit could be seen as musically enforcing that peculiarity in using the sung collect in order to focus the mind of the ministers and worshipper, before the priest-celebrant came to say (or sing) it himself later in the celebration. It is interesting that the Peterhouse Caroline sets refer to them as “Antiphons” – whilst this is not by any ways conclusive evidence, the singing of an antiphon of the size of these compositions would correspond to a liturgical use , namely as musical “cover” for the ministers as they approach the altar (and possibly begin the ceremonies associated with that), as in the former Sarum rite. It seems that the priest-celebrant reverencing the altar was liturgical norm at Durham, and formed part of the complaints against John Cosin lodged by Peter Smart with the Archbishop of York.[69] Whether a genuflection was made here is unclear,[70] and it is unclear as to whether or not the altar is censed.[71] We already see the altar set, with the almsdish, the chalice and paten,[72] as well as the book of the Gospels and the Prayer Book used for the conduct of the service being placed for ease of use. Whilst here we present a modest celebration, it would be probable that the Chapel Royal would display a great deal of its plate (whether on use or not) at 'High' celebrations.[73] In my work, I am unable to ascertain satisfactorily the general position of the ministers for the start of the service – here, I am taking a consensus view that the service up until the collect for the day would be read from the North end. It can be suggested that some factions would have remained in the eastward facing position[74] until sitting for the readings, or may have even read the service from a sedillia or stall. As the rubric categorically states reading this part of the service from the North end of the altar (…and the Priest standing at the north syde of the Table, shall saye the Lordes prayer, with thys Collecte folowinge…[75]), I would believe that the majority of Laudian followers would have followed the rubric at this point, in fear of being reported to the ecclesial and civil authorities.

The puritanical scaremongering encountered in protestant worship certainly is made clear by the Cranmarian inclusion of the Ten Commandments following the Lord's Prayer and Collect for Purity (a hangover from the Sarum Missal of 1542, and certainly of much earlier useage). Even the rubric makes clear the fire and brimstone nature of their inclusion within the liturgy: 'Then shall the Priest rehearse distinctly at the .x. Commaundementes, and the people knelyng, shal after every Commaundemente aske Goddes mercye for theyr transgressyon of the same.[76]'The positioning of the three ministers in this example exemplifies the priest's need to “rehearse distinctly” the commandments, thereby turning to face them, with the deacon holding the text so that it is audible to the people, whilst remaining at the North end of the altar in accordance with the rubrics. Percy Dearmer, whose work in furthering Ecclesia Anglicanum and all things English in the Oxford Movement of the late nineteenth century, concurs with this, however his interpretation “from ancient sources”[77] suggest the North end as being the North side of the altar, which maybe correct for more radical Laudians such as Andrewes, but I do not think the majority of Laudians would have risked such a loose interpretation of the rubric. It certainly rules out the possibility of the Commandments being sung in general,[^14] as the idea of melody during this penitential act would, in puritan eyes, detach the worldliness from it, and would, in their eyes, be against the practice of communal participation in worship.

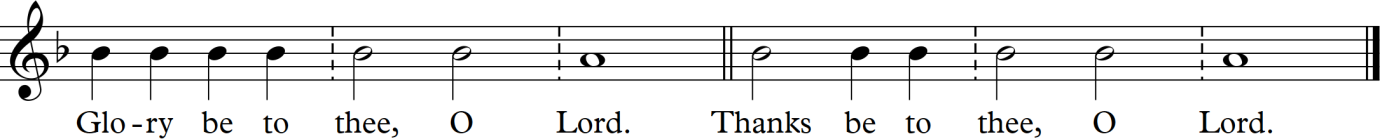

Following on from the reading of the Collects (of the day and for the King) and the reading of the Epistle, the Gospel is read. Whilst the rubrics specify “the priest” to read the Gospel,[78] it can be assumed that in larger foundations these tasks would be shared, as depicted here, at the Sanctuary gates. G.W.O Addleshaw notes that John Cosin approved of the singing of the Gospel, '…on the ground that singing enhanced the dignity of the service and helped the devotion of the congregation'.[79] Addleshaw cites Laudian practice for introducing sung responses before and after the gospel:

This was certainly done at Durham, and most likely the version cited in the Smart condemnation;[81] both Ronald Jasper[82] and Paul Bradshaw[83] concur that Cosin continued this tradition at Peterhouse and once elevated to the episcopate, which influenced the Scottish Prayer Book of 1637, where they were first published.[84] These were certainly a feature of the 1542 Sarum Mass, but were not included in any of the revisions of Church of England liturgies until 1928. There is no record of how the Gospel was sung – it may have followed the Sarum tones (or a variance on that pattern) or have been sung on a monotone. What we do know is that Laudians did venerate the Gospel, 'preferring it before all others',[85] and as such, did treat its proclamation with great reverence. Certainly use of torches (candles carried on processional staves) were common amongst Laudian usage, however the use of incense however varied widely. Whilst evidence suggests that Cosin may have used incense in a similar way to other Laudians as a part of the aesthetic – to sweeten the air and its use a mere processional item, there is some evidence[86] to suggest that more radical Laudians (including Andrewes) would permit censing of the gospel (and other items) in a way reminiscent to the modern catholic tradition of censing.[87] In this depiction, the sub-deacon holds the censer whilst the deacon sings the gospel. The Creed would follow the Gospel – it is likely that in places which embraced a more radical “High Church”, or where the congregation were more willing, it could have been sung: John Merbecke's The Booke of Common Prayere noted certainly provided a setting for the Creed. Whether this would be sung congregationally or by choristers is uncertain.[88] However, Merbecke did provide settings for the offertory sentences which certainly were for a choir or oratory's singing group to sing whilst the bread, wine and alms were presented and the altar prepared. As can be seen in the photographs below, the Laudian preparation of the altar would not have been clear to the people once the items had been presented. The use of bread was an issue which the Laudians held mixed views on – some would consent to use a normal loaf, whilst others (including Andrewes and Laud) would use wafers. Laud's own trial before the Long Parliament takes issue with his using of wafers, however the fact that Andrewes had made use of them for the sacrament continually during his time as Dean of Chapel Royal was not mentioned.[89]

5. The celebration of the Eucharist according to the Laudian Movement part 2

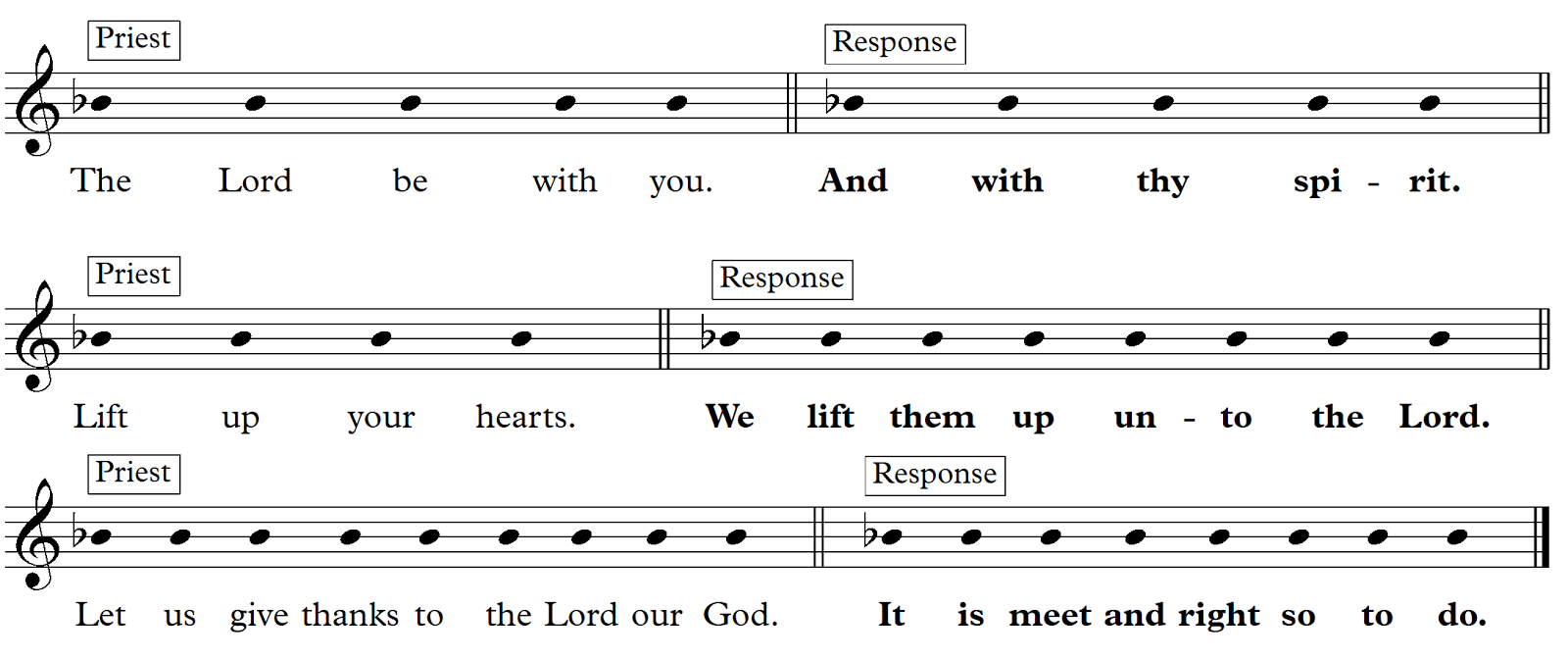

The offertory continues with the preparation of the chalice – including the mixing of the chalice:,[90] which was a contentious issue.[91] It is recorded in many accounts that Lancelot Andrewes at this point made thanksgivings for the presentation of the bread and wine, in the manner of the Tridentine rite, before ritually cleansing his hands using the lavabo.[92][93] The celebration continues with what would have been seen by Laudians as being the first part of the Canon – the intercessions and memoriae, which would have been said. The confession follows. Certainly in more radical celebrations, the introduction to confession would be said by the deacon. It is reasonably certain that this would not be sung, however much this was suggested by Tractarian “musical experts”.[94] However, what was clear was, that following the comfortable words, the priest would sing Sursum Coda - Lift up your hearts.

John Merbecke, in his Booke of Common Prayere Noted set both the Sursum Coda as well as the prefaces:[95]

The preface continues in a similar vein. Evidence suggests[96] that many clergy, especially those influenced by Andrewes, used the more familiar (and more attractive) version from the Sarum rite – indeed, it is this version that is used by the vast majority of worshippers today, and was so attached to the ordinary parts of Merbecke's setting, that many publications include it, replacing Merbecke's own Sursum Coda. [97] The conclusion of the preface following the Sursum Coda is marked by the singing of the Sanctus.[98] The highpoint of the celebration, the prayer of consecration would follow. It is clear that Merbecke intended it to be sung,[99] as he provided tones for it, which certainly would have been used by the likes of Andrewes and his followers. Here, for some, would be the ceremonial high point – the priest-celebrant taking into his hands the bread and wine, raising them[100] and breaking the bread. Again, it is clear that different practices were carried out in regards to this, and to the surrounding conduct. The Roman Tridentine rite marks the Consecration with ringing of the Sanctus Bell,[101] and incensation at the point of elevation. Marianne Dorman, in her research regarding Andrewes' practice, finds that '…[he] restored the appropriate manual acts during the prayer of consecration.'[102] This, in my mind, is ambiguous – did Andrewes restore the manual acts of the 1549 book, or those of the Sarum Missal of 1542? It is here that Dorman makes it clearer:

It is in the Canon that Andrewes, Overall, Cosin and others digressed distinctly from the 1552 Holy Communion service. After the Sanctus came the prayer of consecration followed by the prayer of oblation, the Lord's Prayer, the Prayer of Humble Access and the Agnus Dei.[103] At the Consecration…there is the comment that the 'words of institution, “this is my Body … this is my Blood” with the accompanying manual acts are in the ancient liturgies such as SS. James, Basil, Chrysostom and Clement', whilst the invocation to 'be partakers of His most blessed Body and Blood' are the very same words that St. Ambrose used. [104]

It seems that Andrewes followed the interpretation of Richard Hooker's via media fervently in using the 'catholic'[105] forms of manual acts. We must therefore infer that the use of incense during the consecration in a manner reminiscent of the Tridentine rite could plausibly have taken place (however, I am careful to realise, from own experience, that there are ways of things liturgically not appearing as they seem in order as to not arouse too much suspicion from a congregation). The Canon being over, the communion would be distributed at the rail, kneeling. The priest-celebrant would consume any remnant sacrament at the altar. Following the Prayer of Thanksgiving, the Gloria in Excelsis would be said or sung. It seems that even Andrewes, one of the most radical of the group, agreed with the positioning of this hymn at the end of the Eucharist, believing it to be 'the most appropriate place to sing the angels' song, for never are we as close to them than when we have received Christ in the Sacrament.'[106]

What we see liturgically[107] is something of a counter-reformation. We see a liturgy directly at odds with the neo-Protestant belief. We see too some ideas on musical participation – particularly the introduction of the responses to the Gospel, the continued use of the Sarum tones for the Sursum Coda and preface, and the encouragement by John Merbecke of singing the Prayer of Consecration. What we do not see however, is a wider movement within music. Why is that?

6. "So why not Music?" - Laudian reforms and music (or lack thereof)

What we have seen so far is a movement that was factional; a minority within the wider church and certainly only active in places which were, by their own definition, extra-parochial.[108] In the present climate, we could term it as a “them and us” situation: these foundations following a High Church interpretation whilst the parishes followed fast diverging neo-protestant groups. Of course, what has to be remembered is that Laudianism did not permeate all English Cathedrals and other Foundation status churches or chapels. Certainly there is wide evidence to support that William Laud's own views were not widely held within his diocese or at his Cathedral, as can be seen by reactions to his rite for and his own conduct at the consecration of churches[109]within his diocese.For us to understand some of the reasons why liturgical music did not play such a key part in the Laudian experiment, we need to look at what happened around the time of the Act of Uniformity in 1559.

Queen Elizabeth I cannot be described as a puritan. As we have discovered previously, her Chapel Royal worshipped in a way which we would identify as “High Church”. The music of the Chapel Royal would be based solely on the canticles, or pieces defined as anthems by court composers such as Tallis and Byrd. However, what we would find in parish churches is something completely different. Metrical Psalms were fast becoming popular forms of expression with the ever dominant neo-protestants within the Church of England. Elizabeth was aware of the growth of this phenomena, and whilst wanting to continue what she, like her chaplain Lancelot Andrews, saw as the “beauty of holiness” within worship, she knew that, for the good of the Church – her Church, she would have to, at least publically, tolerate the Calvanist and Knox-ian tendencies sweeping through the at the grass-roots level. In the summer of 1559, following the enactment of the Act of Uniformity, a Royal Visitation took place in order to ensure the general use of the new Prayer Book, and to investigate any issues not dealt with under the act. As regards to music, Elizabeth was clear – any foundation supporting church music would be maintained, even at the parish level. But, she did make one concession, in relation to metrical psalms:

And that there be a modest distinct song.[^3), so used in all parts of the common prayers in the church, that the same may be plainly understood, as if it were read without singing, and yet nevertheless, for the comforting of such that delight in music, it may be permitted that in the beginning, or in the end of common prayers, either at morning or evening, there may be sung an hymn, or such like song, to the praise of Almighty God, in the best sort of melody and music that may be conveniently devised, having respect that the sentence of the hymn may be understood and perceived.[^4)

This statement would have a significant impact on the development of church music in the coming centuries, and was used by both Puritans and Laudians, High and Low-churchmen to advance their cause. During Elizabeth's reign, the nation's religious ideology turned wholly towards a protestant reformed tradition. By the time of the accession of James VI & I, the church is one which is protestant. The flourishing of the Laudian experiment under the first two Stuart monarchs gave great hope for music within the life of the church. In many dioceses, work was undertaken on repairing and replacing organs damaged or run-down during the previous decades[^5), however in many places this caused great consternation. The Vestry[^6)of St Michael, Crooked Lane, London drew up a hefty of list of “Reasons against the Organ”, citing a myriad of reasons including tradition against the organ, the cost of maintenance and an unnecessary tax burden upon the populous. It seems that the Vestry won the day, and no organ was built. Indeed, prior to the Civil War, records suggest that very few churches within the capital had an organ, and this was similarly the case in many parts of England and Wales[^7). There were, for church musicians, few signs of optimism during the period.

Certainly, church musicians had a great deal to fear – neo-protestant denunciations came thick and fast from within the church and academia. The Reverend John Case, Fellow at St John's College, Oxford, complained greatly of the need for hired singers with their “cunning and exquisite music”[^8)- certainly a discouragement for men within the profession. With condemnation coming from one of the two universities, where little more than a century earlier, Cardinal Wolsey has established his 'Cardinal College'[^9)to produce great men of letter and arts for the church and society, it is no wonder that there seems to be little impetus for church music in this period. Within the wider church, there was little impetus for church music. Bishop Robert Horne of Worcester[^10)notably banned organs from his diocese from being played, forbidding their restoration, and in many cases ordering their destruction. He also forbade singing that drowned, lengthened or shortened any word or syllable, or repeated words of sentences[^11). What we clearly see here is a social and cultural gap between court and country, which is not brought politically together until the Restoration in 1660. Whilst parishes under their neo-protestant ministers began to accept, even adore their new found Protestantism, court religion remained reasonably unchanging: we can safely assume that this would not only be in figures and thought but also in choices of music[^12). Nicholas Temperley recalls that Elizabeth I “withdrew”[^13)during the religious service prior to the State Opening of Parliament because of the inclusion in the liturgy of a Metrical Psalm.

The notable attempt at incorporating music-making within the Laudian tradition was led by John Cosin. Cosin certainly was a follower of Lancelot Andrewes in liturgical conduct and held almost as radical views (for the time). Certainly, to neo-protestants and even some within the Laudian group, Cosin would have been controversial. Whilst his conduct at Durham had ended with stalemate between the Prince-Bishop and the King, for a time at Peterhouse, Cosin was able to lead the College's worship following the principles of Laudianism, influenced by Lancelot Andrewes. In terms of music, Cosin is the primary figure within the Laudian group. His innovations at Durham, including the introduction of responses to the Gospel proclamation, seem to have been part of liturgical life at Peterhouse during his tenure as Master. Certainly at Peterhouse, Cosin had more freedom in regards to his liturgical practice, and would be able to combine the Laudian “beauty of holiness” through music and the liturgy. There is evidence that Cosin instigated a sung Eucharist in a style that would be familiar to prayer-book Anglicans today. The Peterhouse part-books contain material for the Sanctus , Gloria in Excelsis and responses to the Sursum Corda [110] What is interesting is that there is no sung setting of the_Kyrie Eleison_or responses to the Commandments, indicating that Cosin was not as radical as Lancelot Andrewes in additions to the printed liturgy. The settings in the Peterhouse part-book are by a medley of composers of the period, include items by Tallis, Dering,[^15] a “Mr Ferrabosco” – most probably Alfonso Ferrabosco the younger,[^16] and the complete_Missa Sine Nomine_by John Tavener.[^17] The importance of the Eucharist at Peterhouse is certainly clear by the fact that Cosin is facilitating a sung liturgy, and it can be assumed that this would be a “principal celebration”[^18] rather than an extra service, however there is evidence to suggest that the Eucharist was a service for members of College only, and not open to the wider public.[^19] This may also explain how some English Morning Canticle settings have come to be translated into Latin. Within the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, Prayer Book service were permitted to be held in Latin, protected by the Canons of 1603.[^20] It seems that whilst Cosin was at Peterhouse, the tradition was secure, although there is no evidence that it spread further, and once deprived of the Mastership in 1643, an ecclesial cleansing of Laudian ornaments, practices and rites was conducted.

7. The failure of the movement?

The failing of the Laudian movement as a whole to enhance the musical life of the church is evident of its factionalism. It currently can be judged as not having '…a distinctive […] practice in church music',[111] and this is even more clear when looking at the movement's liturgical impact. Whilst, in some ways, the Laudians were well placed to have an effect on the wider church, being positioned in offices of state and being dignitaries within the court and church, the movement was lacking in unity and common appeal. If we compare it to the more successful Oxford Movement of a century and a half later, whilst we see some similarities regarding its conception and its initial foot-hold within society, there are notable differences. The lack of enthusiasm by the laity is a reasonable sign that the movement had failed in attempting to convert a wider audience to its viewpoint – it remained “established” religion, which certainly was not the case for the first and second generation Tractarian clergy. Certainly during the early Elizabethan period, the Catholic viewpoint was still held by a great many people, so a challenge to the rampant neo-protestantism may have been more successful. The lack of a permanent educational establishment[112] espousing the Laudian principle[113] certainly deprived it of further followers, which in turn would mean that certain aspects of the church's life would be under represented. If we look at the influence of the Oxford Movement on music within the church, it is reasonably quiet within the first decade or so, however by the late nineteenth century, there was enough interest in Gregorian Chant for an association to be formed[114] for its study. By 1906, Percy Dearmer had compiled The English Hymnal as an Anglo-Catholic hymnal,[115] which would mould generations of High Anglicans. Certainly technological and communicatory advances, as well as the rejection of “establishment” by the early Tractarians, provided a more secure base for the Oxford Movement to grow. Hypothetically, if both the political and ecclesial situations had been more stable, Laudianism may have been a more successful movement for church music, as there would have been less tension between the neo-protestant groups and the Laudians, which may have meant the restoration (or creation of new) organs and the re-vitalising of parish music beyond the Metrical Psalms (as was the case with West Gallery music in the eighteenth century).

Whilst having given several reasons why the Laudian movement did not grow, the principal reason for the movement's failing was the English Civil War. The Laudians were on the wrong side – backing Charles I. The growing hatred of the monarchy following eleven years of direct governance by the King,[116] tied in with parliamentary displeasure and regional grievances left the Kingdom of England in an diabolical mess, from which if took several generations to avail itself of fully. Within the church, an almighty cat-and-mouse game continued, with Laudians and suspected “High Anglicans” being deprived of their livings and being exiled with the episcopacy being abolished in 1646. For Laud, exile was not an option – because of his own political deviousness[117] and his personal association with Charles I, he was executed by the Long Parliament in 1645. His ecclesial policies were not as extreme as Lancelot Andrewes', but because of Laud's venomous zeal in depriving neo-protestants from livings, and his enforcement of certain Laudian practices coupled with his extreme politicking, he became the first Anglican Martyr. He was certainly not the last during the period – indeed, 30 January 1649 saw the beheading of Charles I. He, so far, has been the only Anglican ever described as a “Saint”[118] – however, the Church of England no longer holds him in high esteem, and is “commemorated”[119] in its Kalender.

The end of the Civil War saw a fragmented peace within both church and state. The Savoy Conference of 1661 can be seen to be the end of accepted radicalism for both neo-protestants and Laudians.[120] At the conference, episcopal polity within the Church of England was “re-established”, and was protected under law.[121] The articles of Elizabeth I were to be adhered to, but the mood of the nation had changed. No longer was it a country that was Catholic – it had been transformed by the puritanical Protestantism of Calvin and Knox, and formed during a period of apathy and anger towards the establishment of King and Church. The compromise, found in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, demonstrates moderation between both High and Low Anglicans.[122] Whilst bastions of Laudian principals (mainly Cathedrals and some smaller foundations) could continue in worship following a notably decreased form of ceremonial and ritual, the majority of the nation would worship according to the protestant forms interpreted “as read”[123] in the rubric. Nicholas Temperley interprets the musical division caused by this settlement as certainly being influenced by class – the working class, attending parish churches, on the whole would be exposed to more Low Anglican tendencies, whilst the educated and aristocracy would worship in places which represented the continuance of establishment, and certainly would have contained some Laudian influences. For music, the political victory of the Low church wing led to nearly two centuries of lowered standards of church music making.[124] Whilst composition began to grow following the restoration,[125] the performing standards of church music were abhorrently poor, only beginning to be challenged and improved in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[126] The rise in popularity of metrical psalmody contrasted greatly with the composition of works for the Chapel Royal and State ceremonies, certainly generating a greater divide between the wider nation and London, as home of the court and a centre for talented and able young men.[127]

So what then of the Laudian movement? What was its lasting effect? As I have demonstrated, its musical legacy is feeble at best. Other than the Non-Jurors of 1688, major dissent is quelled within the “High Church” faction of the Church of England. Its failure to permeate into the majority of parish churches certainly would seem to demonstrate that the movement was insular, establishment based, and certainly inter-dependent upon the reliance of the Monarch. Its liturgical legacy can be seen rubrically within the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, and in wider noted customs of the Church – as I described at the start of this essay, “the altar and the items upon it, communion wafers, vestments and even the cloth covering the altar”. That these became accepted even by the most vehement of Low Anglicans is a tribute to the Laudians attending the Savoy Conference of 1661 and their spirit of compromise, which in effect, sacrificed any real chance of their movement gaining further impetus. However, the widely held view that the Church of England became more of a neo-protestant movement following the Act of Settlement can certainly be challenged. Within major centres of population, and certainly within the South-West and North, the Church of England expressed itself in a way modern churchman would describe as protestant. However, it seems that Laudians did continue, and indeed grow their movement in parts of the Church. The appointment of Robert Morgan, Humphrey Lloyd and Humphrey Humphries as successive bishops of Bangor,[128] and George Griffith, Henry Glenham, Issac Barrow and William Lloyd as bishops of St Asaph, all of whom had Laudian tendencies, demonstrated the fervency of the “High Church” movement in North Wales. The post-Restoration Welsh bishops were deeply opposed to Protestant dissent, a characteristic trait of High Churchmanship. It is also significant that advocates of the Jacobite cause were active in Wales well into the eighteenth century, while the fact that bishops William Beveridge of St Asaph, George Bull of St Davids and Christopher Bethell of Bangor were sympathetic to High Churchmanship allowed it some freedom to develop in three of the four Welsh dioceses.[129] The Venerable D. Efion Evans, an ecclesiastical historian of the Church in Wales, discovered evidence of the prevalence of the Laudian movement in parts of north Cardiganshire (Ceredigion) in periods pre-dating the Oxford Movement[130]20). The western edge of Wales, particularly Cardiganshire was not vibrant, having no real population centre nor a seat of learning prior to 1822, and held no major transport hub. It therefore is difficult to fathom how such a tradition could be present prior to the rise of the Oxford Movement if it was not already there in continuation from the Laudian era. It is clear that whilst centres of population and places of scrutiny (such as the Cathedral at St Davids), any sort of High Churchmanship would have been held at bay, or at the most, quietly tolerated, for there to be a prevalent tradition pre-dating the Oxford Movement in Ceredigion, it could only be a remnant of Laudian High Church worship of the seventeenth century.

8. Epilogue

The legacy of the Laudians certainly is a varied one. As a movement within the church, its short-lived, elite institutionalism was certainly its major failing. Its role as a divide amongst the English prior to the Civil War is important; however it is my view that the personality of William Laud rather than the wider Laudian movement can be held responsible for the polarisation of the country. Its impact upon music is limited and disappointing. That there is a dearth of repertoire from this period (both anthems and canticles) emanating exclusively from the movement is telling of both the conservatism of the movement and its overall lack of interest (with some exceptions) in the music performed in the liturgy. It appears that the role of music within Laudian liturgies was to “go through the motions” of the office – not being, in its own right, associated with the “beauty of holiness” movement being propagated. The work of John Cosin is to be applauded in continuing to enrich the Church of England's musical life during the period – if the political situation had been different, and Civil War had not taken place, then it may have been possible for further Laudian foundations to flourish, which certainly would have enriched the musical life of the English church and would certainly have kept pace with change with the wider musical world.

However, without the failure of the Laudian “experiment”, the renaissance of catholicity within the Church of England from the middle of the nineteenth century would have been impossible. The Oxford Movement provided a firm impetus for music within the liturgy of the church, through the founding of the Plainsong and Mediaeval Music Society, the inclusion of nineteenth century Latin mass settings by French, Germanic and Italian composers in High London parishes,[131] the production of the English Hymnal by Dearmer and Vaughan-Williams, and later (through the work of the Roman Catholic musicians at Westminster Cathedral in the early and mid twentieth century) the inclusion of Catholic composers in Anglican choral services.

The Laudians are an underappreciated movement within the Church of England's long history. In terms of musical quality – especially relating to performance standards and aesthetic range – the Laudians' attitudes to music have found some fulfilment in current day Cathedral worship. However, more work on their liturgical and musical contribution is needed for us to fully understand their rich, yet sadly underestimated legacy in enriching the worship of the Church of England through the “beauty of holiness”.

A movement centred around the University of Oxford that argued for the reinstatement of traditional rites and ceremonies within the Church of England, among which the centrality of the Eucharist or “Mass” was paramount. ↩︎

A term used (especially in the lectionary) to distinguish the main service (or one that most people would attend), from others. This would ensure that the most associated readings for that particular day would be read at the main service. ↩︎

The Alternative Service Book: Services authorized for use in the Church of England in conjunction with The Book of Common Prayer, Oxford, The University Press, 1980, 113 ↩︎

The words of institution are a combination from the Last Supper Narratives from the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke, with the Pauline account of the Last Supper from 1 Corinthians 11: 24-25. ↩︎

Many Cathedrals were slower to follow suit – for instance, it was not until Ronald Jasper was appointed Dean of York in 1975, having served as Chairman of the Liturgical Commission, that the Eucharist (in a modern language experimental format being trialled by the Commission) was acknowledged as being the Minster's “Principle Service”. ↩︎

The Tridentine Mass is the 'traditional' Eucharistic service of the Roman Catholic Church. There were numerous instances of celebrations of this, from either the English Missal or from the Catholic liturgy directly. Some continued the practice, as at Papal celebrations of the time in Rome, of non-communication of the public. ↩︎

As is demonstrated by the 1662 Communion liturgy. ↩︎

Most of these sources would be deemed “illegal” by the Church, although most diocesan bishops turned a blind-eye to liturgical tinkering in parishes, so long as there was no public controversy. ↩︎

In the 1928 Order, A Summary of the Law was included, text taken from the Gospels being the words of Christ, concluding with the text used after the tenth commandment. The second alternative was the 'Kyrie' – the first time since before the reformation that is was included in a Church of England liturgy. ↩︎

The Benedictus and Agnus Dei will be detailed later in this section. In the 1928 order, the Benedictus was permitted – although was published separately from the Eucharistic order, likely so that it did not become common place. The Agnus Dei was not published at all within the book – musical settings of the time did include it, so it is likely that it was treated as a 'Fraction' anthem, as indeed was its intended original purpose. ↩︎

Hence, the now popularised 'Stanford in C and F'. The majority of the service being written in C, whilst the Benedictus and Agnus Dei were written later in the key of F. This is the case with the services in A and B flat also. ↩︎

Ireland goes one further in his composition, having included a sung Lord's Prayer, incidentally placed in the copy before the Agnus Dei – the 1662 Communion service places it after the communion of the people. ↩︎

Ed. Rimbault, E.F “The Book of Common Prayer with Musical Notes as used in the Chapel Royal of Edward VI. Compiled by John Merbecke, Mus.Bac. Oxon. Organist of St George's Chapel, Windsor. AD 1550.” London, J. Novello, 1845. ↩︎

A phrase used by modern liturgists for the praxis of Eucharist – the practical application of theology, ritual and belief within the liturgy itself. ↩︎

If, and when, the Church of England becomes disestablished, the roots of a separate “Anglican” identity, rather than that of an “Established Church”, will be found in the early to mid-1960's with the archiepiscopate of Michael Ramsey, the publication of John Robinson's Honest to God and a wider group of cultural and academic persons openly linking themselves to this movement. ↩︎

“leading” was most probably a polite euphemism for sole domination. ↩︎

Later known as “The Ecclesialogical Society”, whose aims were the study of Gothic Architecture and Ecclesiological antiques, and who played a great role in the design of Victorian churches. ↩︎

Traditional celebrations of the Eucharist are offered facing “liturgical East” – that is, in front of an altar, facing away from the people. ↩︎

For instance, at the Eucharist, the Sub-Deacon would read the Epistle (or First reading), rather than a lay person. This makes some sense in a traditional (or “Tridentine”) celebration, but would be exceptionally odd, and even insulting to the laity in the new rites. ↩︎

This is what was envisaged, and indeed was realised in some places: for Roman Catholics, the Metropolitan Cathedral in Liverpool, and for Anglicans, St Paul's, Bow Common realise the intended liturgical space that all were meant to achieve: very few places managed this change satisfactorily. Images of these can be found at http://www.liverpoolmetrocathedral.org.uk/content/Visitus/TheCathedral.aspx and http://www.stpaulsbowcommon.org.uk/about-our-church/a-very-flexible-space/founding-principles/ ↩︎

Depending on how liturgically open the particular church was, this could mean anything from reading one of the lessons at the Eucharist, to presenting the bread and wine to the priest at the offertory, or even administering the chalice during communion. ↩︎

Those outside of Oxford and Cambridge, and the monastic community at Mirfield in Yorkshire. ↩︎

Which had been ideologically entrenched within them during their theological training. ↩︎

Ira D. Sankey (1840-1908) was a Methodist singer and composer, noted for writing hymnody and songs which are noted for over-sentimentalism. ↩︎

Rutter, J. Communion Service (Series 3) Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1972, 2 ↩︎

Greater Churches are establishments which operate liturgically, and often musically, in a similar way to a cathedral, although they have retained their function as a parish church. ↩︎

Such as All Saints, Margaret Street and St Mary's, Bourne Street. ↩︎

Rite A was the modern language text of the Eucharist. ↩︎

A full copy of Piccolo's Canterbury Mass is included in Appendix A. ↩︎

For Canterbury, this service has an added resonance as it is celebrated by the Archbishop of Canterbury, whose Christmas sermon is broadcast (in part) on radio and television. ↩︎

A full copy of The Kent Service is included in Appendix A. ↩︎

For Howells and Darke, this was setting the Sursum Coda – “Lift up your hearts”, which precedes the Sanctus. More often than not, this was sung to the ancient Sarum tones. ↩︎

This is still the case, however with further rubrical developments in Common Worship, it has been easier for cathedrals and churches to form their own “identity of worship”, which will speak volumes as to how worshippers are treated or expected to express themselves during the liturgy. ↩︎

There is evidence to suggest that these took place using the Alternative Service Book, however, whether or not the liturgy stuck entirely to what was contained within the rite is unclear. ↩︎

Unfortunately, the “electronic” nature does not (on the whole) relate to modern idioms of either classical or popular music, rather that Sibelius notation software has been used to create an accompaniment and is played through the sound system. There are liturgical experiments involving the use of dance and trance music, and some of these have been successful, but are unlikely to find their place in regular Sunday worship any time soon. ↩︎

A work of Gabriel Jackson's, The glory of the Lord, written by commission of Westminster Abbey for the visit of Pope Benedict XVI in 2010 demonstrates the virtuosity of a modern “cathedral” choir. A copy of this piece is enclosed with this paper as an aide-memoire. ↩︎

Such as the Responses from the Daily Office. ↩︎

The Preface to the Declaration of Assent, accessed online at http://www.churchofengland.org/prayer-.worship/worship/texts/mvcontents/preface.aspx 04/01/2013 ↩︎

The 1661 Savoy Conference was a significant liturgical discussion that took place after the Restoration of Charles II, in an attempt to effect a reconciliation within the Church of England, resulting in the preparation and publishing of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. ↩︎

Addleshaw, G.W.O, The High Church Tradition, Faber & Faber Limited, London, 1944, p.13 ↩︎

Harper, J., The Forms and Orders of Western Liturgy from the Tenth to the Nineteenth Century: A Historical Introduction and Guide for Students and Musicians, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1991, p.176-177 ↩︎

The Catechism of 1604 refers to the 'Supper of the Lord' as a Sacrament, thereby removing any contentiousness from referring to it as such within this work. ↩︎

It is certain that the idea of forming the Daily Offices into two distinct morning and evening liturgies came from Quiñones' work. ↩︎

From this work, the Prayer of Humble Access derives, most likely in the position found in the 1549 liturgy. It was subsequently moved to before the Prayer of Consecration in the 1552 edition, remaining in that position in the 1662 service. ↩︎

Kyrie, Gloria, Sanctus, Benedictus and Agnus Dei. ↩︎

13th century Sarum Kyrie in Baxter, P. Sarum Use: The Ancient Customs of Salisbury, Spire Books, Reading, 2008, p.102 ↩︎

Merbecke's Kyrie Eleison, from “The Prayer Book noted” in in Baxter, P. Sarum Use: The Ancient Customs of Salisbury, Spire Books, Reading, 2008, p.102 ↩︎

This was the hope – however, following the re-invigoration of the catholic movements in the nineteenth century, those who followed the ideas and works of Percy Dearmer (who was influenced by Laudians as well as the English church of the Middle Ages) instigated re-examination of the prayer, being able to accept the separation of the Prayer of the People and the Consecration as being one act interrupted, however the Consecration would be followed immediately by the Prayer of Oblation before carrying on to the distribution of communion. ↩︎

Elevation had been removed from the 1549 book, but it still instructed the priest to take into his hands the bread and wine. By 1552, no such action was mentioned. ↩︎

As envisaged in the 1549 Book, and not as enacted prior to it – certainly it is wishing to concede certain actions to those of a High Church belief: the priest is to take into his hands the bread and wine, and then also to lay his hands upon all the vessels containing them (in the manner in which we would in this era do at the point of ἐπίκλησις, the Epiklesis – asking the Holy Spirit to come down and set aside the bread and wine so that it may be the Body and Blood of Christ). ↩︎

Chasuble, dalmatic and tunicle ↩︎

This would be transitory as the Canons of 1604 specified the vesture of copes, stoles and surplices at the celebration of Holy Communion. ↩︎

The Anglican term 'dignitary' is used for those below the episcopal state who are “higher in rank” than other priests, through the conferment of an office, such as a canonry, archdeaconry or deanery. It can also be used to describe bishops and archbishops. ↩︎

The 'common mind' in this circumstance would have been a number of the residentiary chapter. ↩︎

Certainly this would have been the case in Bishop Lancelot Andrew's private chapel. It would stand to reason that his chaplains and other domestic clergy would have approved of Andrew's view on the celebration of the sacrament, thereby also creating a 'common mind' on it. ↩︎

In using the term 'common use', I mean, actions and ceremonial that was noted in several sources. ↩︎

Stevenson, Kenneth. “Worship and Theology: Lancelot Andrewes in Durham, Easter 1617” in International Journal for the Study of the Christian Church. Volume 6, Issue 3, Routledge, Abingdon, 2006. p. 223-234. ↩︎

Dorman, Mariane. “Andrewes and English Catholics' Response to Cranmer's Prayer Books of 1549 and 1552”. given at the Reformation Studies Conference, Westminster College, Cambridge. 1999. Accessed online at http://anglicanhistory.org/essays/dorman2.pdf on 18/03/2013 at 15:26. ↩︎

Addleshaw, G.W.O, The High Church Tradition, Faber & Faber Limited, London, 1944. ↩︎

This explains the conflicting accounts of Laudian worship, as rubrics can be interpreted (and mis-interpreted) to suit one's own liturgical viewpoint or need. ↩︎

The Diocese (at that point) stretched from St Davids in the west, to the edge of the Welsh Marches (only several miles from Hereford) in the east, and from Aberystwyth in the north to Swansea in the south. As a geographical area, it covered what is now termed as Mid-and-West Wales. Up until the late nineteenth century, it was highly common for bishops and dignitaries to rarely be present in their territory – either they would be at a living nearer the capital, or would find other ingenious ways of being absent (as mocked by the character of Prebendary Dr Vesey Stanhope in Trollope's Barchester). It was also highly common for bishops and dignitaries to be installed “by proxy”, using either the Letters Mandatory or Patent for them or their commissary (delegated representative) to take possession. In Laud's own case, he was Dean of Chapel Royal during his episcopacy at St Davids, so would rarely have ventured to either diocese or cathedral, but certainly would have imposed his own views being Bishop of the See, either when visiting or via appointments of senior clergy. ↩︎

Whether it was bread or a communion wafer ↩︎

That is, the adding of water to the wine ↩︎

In this essay, I will refer to the sacred ministers by the titles used by Tractarians as so to distinguish their liturgical ministries. It is clear that priest and deacon would have been referred to by some Laudians, however others would have distinguished the priest-celebrant from other assisting clerics by referring to them as 'ministers', in line with the 1552 and 1559 rubrics, later enshrined in the 1662 rubric. ↩︎

Temperley, N. Parish Church music under the first two Stuarts in The Music of the English Parish Church, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge & London, 1979, p. 51. ↩︎

In the manner that could have been found in the Graduals and associated musical resources of the Sarum Missal of 1542. ↩︎

A prayer or prayers appointed to be said at services on a particular day or occasion. ↩︎

Webster, Peter, The relationship between religious thought and the theory and practice of church music in England, 1603-c.1640. PhD thesis, University of Sheffield., 2001, p.170. Accessed online at http://sas-space.sas.ac.uk/3208/ ↩︎

'Articles…to be exhibited by his Majestie's Heigh Commissioners, against Mr. John Cosin' in ed. Ornsby, G. The Correspondence of John Cosin, Surtees Society, London, Volumes 52-55 (1868-72) I, p.165. ↩︎

It certainly looks like there were genuflections during the Prayer of Consecration ↩︎

Because of the lack of clarity in the charges against Cosin, I am not a hundred per cent certain that he did not cense the altar at the start of the liturgy. However, I ere on the side of caution, and in the appendix containing the photographed liturgy, I have not included that possibility. ↩︎

Although, they would be barren of bread and wine at this point ↩︎

Those being principal Holy days or other days of importance such as the commemoration of the Accession, Coronation, or other state event. The layout of plate in this manner is still carried out in the way at Chapel Royal, and was the case at the 1953 Coronation – the plate was placed near the Sovereign's faldstool, and was brought to the altar for the communion service. ↩︎

As indeed became the Tractarian practice. ↩︎

1559 Communion Service – rubric prior to the recitation of the Collect for Purity. http://justus.anglican.org/resources/bcp/1559/Communion_1559.htm Accessed 25/03/2013, 19:59. ↩︎

1559 Communion Service – rubric prior to the recitation of the Ten Commandments. http://justus.anglican.org/resources/bcp/1559/Communion_1559.htm Accessed 25/03/2013, 19:59. ↩︎

As he and others, including Clement Skillbeck attempt to justify in works published by the Alcuin Club during the early twentieth century. ↩︎

1559 Communion Service – rubric prior to the reading of the Gospel. http://justus.anglican.org/resources/bcp/1559/Communion_1559.htm Accessed 25/03/2013, 19:59. ↩︎

Addleshaw, G.W.O, The High Church Tradition, Faber & Faber Limited, London, 1944 p. 45. ↩︎

These responses are evidence of inherited tradition within church music, usually coupled with the use of Merbecke. ↩︎

'Articles…to be exhibited by his Majestie's Heigh Commissioners, against Mr. John Cosin' in ed. Ornsby, G. The Correspondence of John Cosin, Surtees Society, London, Volumes 52-55 (1868-72) I, ↩︎

Dean of York 1975-84, Chairman of the Liturgical Commission 1964-80. ↩︎

Professor of Liturgical Studies, University of Notre Dame 1984 - present ↩︎

Jasper, R.C.D, & Bradshaw, P.F, A companion to the Alternative Service Book 1980, SPCK, London, 1986, p.256. ↩︎

Sparrow, A. A Rationale on the Book of Common Prayer of the Church of England, London, 1672 p.159. ↩︎

Certainly Addleshaw notes on several occasions in his work The High Church Tradition that Andrewes was conducting censing in the manner recommended in the Tridentine rite. As this would have taken place mainly at the altar, and close examination would have been difficult by detractors, the only reason for accepting this as truth would be Andrewes notoriety for extremism, however, the censing in accordance with the Tridentine rite could be accepted through via media as part of inherited tradition. ↩︎