The Caroline Liturgical Movement

[REVISED MAY 2018]

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer bequeathed to the Church of England, and the entire Anglican tradition, an ambiguous liturgical legacy. He was both a liturgical genius and, to be blunt, from the Catholic perspective, a purveyor of eucharistic heresy. This put later Catholic-minded Anglicans in a very curious situation: Cranmer had to be retained in some sense, since to be Anglican, historically, has meant adherence in some way to the Book of Common Prayer in its various incarnations. [2]

What the 15th century Byzantine patriarch and theologian George Scholarios ((†c. 1473) wrote concerning Origen (the posthumously anathematised “father of orthodox theology”) can be applied in some analogous way to the liturgical work of the first Protestant Archbishop of Canterbury:

The Western writers say, “Where Origen was good, no one is better, where he is bad, no one is worse.” Our Asian divines say on the one hand that “Origen is the whetstone of us all”, but on the other hand, that “he is the fount of foul doctrines”. Both are right.[3]

Louis Bouyer, a Roman Catholic sympathetic to Anglicanism, grappled, not unlike Scholarios, with the enigma of Thomas Cranmer, at one and the same time liturgical genius and exponent of Eucharistic heresy. Bouyer concurred with the judgment of Dom Gregory Dix, who “established irrefutably” that both the 1549 and 1552 liturgies express (the first ambiguously, and the second more explicitly) “a doctrine which is not only 'reformed' but properly Zwinglian.” Bouyer described the 1549 liturgy, despite its ambiguity, as an “incontestable masterpiece” , successfully[4] “retaining even in its details the schema of the ancient Roman eucharist.” Bouyer even went so far as to compare Cranmer's work with “the remodelling of the ancient eucharists that we have seen come about in fourth century Syria.” [5]

It has been well established, by Dix and others, that Cranmer's views were heterodox and “Zwinglianizing.” It is an entirely different question, however, whether or not he succeeded in making his views loud and clear in the 1549 Mass itself. The new Liturgy, since its very first appearance, seems to have been interpreted in various senses by both the moderate “Henrician Catholic” party (represented by Bishop Stephen Gardiner), who were content to use the rite according to a basically orthodox Western Catholic understanding, and the more extreme reforming party, who thought that the form of the Liturgy was still far too “popish.” In fact, as Dix argues, “what had largely assisted the general misunderstanding of 1549 was its retention of the traditional Shape of the Liturgy.” [6]

The genius which Bouyer discerned in Cranmer's 1549 work was to be destroyed only a few short years later. If Cranmer's true eucharistic doctrine was ambiguous in his first attempt at revision, it became crystal clear in his second Communion Office. His radically re-arranged 1552 liturgy was designed precisely both to appease the more extreme Reformed voices, and to make an orthodox Catholic interpretation of his work impossible. The new eucharistic prayer was a mere shell of the 1549 one, no longer resembling a classical Christian anaphora of any kind. It retained a great deal of Cranmer's familiar prose, but in a radically different form.

By another ingenious (yet completely un-traditional) rearrangement, Cranmer was able, with great care, to edit away all notion of a Real Presence of Christ in the elements of bread and wine. Likewise, Cranmer disconnected any notion of sacrifice or oblation from the elements of bread and wine themselves, by transferring all sacrificial material in the 1549 Canon into an optional post-communion devotion. No longer is there a mystical, propitiatory offering of Christ as Victim, but a mental remembrance of his one Sacrifice on the Cross, and an appeal to Christ “the only Mediator and Advocate” that we may enjoy the benefits of the Cross through faith. If any offering is made, it is not connected to the one Sacrifice of the Cross, nor with the bread and wine, but with the offering of ourselves in thanksgiving to the Father for the redemption wrought by the Son.

The break with the eucharistic doctrines of Cranmer, and his deformed liturgy, which was begun early in the reign of Elizabeth, was widened considerably during the subsequent reigns of James I and Charles I. Since the beginning of the reign of Queen Elizabeth, many Anglican divines, says W. Jardine Grisbrooke, “continuously devoted their energies to attempts at revising it, amending it, or even, in the last resort, replacing it by a different rite.” Many High Churchmen discovered ways to[7] improve the 1552 shape through altering the order of the prayers (after the 1549 pattern) as well as ceremonial and musical enrichments. Thus, in the words of G.W.O. Addleshaw, against Cranmer's radical intentions, “they interpreted the Prayer Book and gave it form and meaning; under their hands a protestant service book was transformed into a catholic liturgy; they discovered its beauties; they loved it and were ready to die for it.”[8]

Thus, we begin to see “the development of a specifically and distinctively Anglican liturgical type,” through reforms all in the direction of 1549 and the ancient Liturgies of the Church. Alongside a re-emphasis on doctrines of Real Presence and[9] Eucharistic Sacrifice (albeit not in the full Catholic sense), a distinctive High Church Anglican eucharistic piety began to develop, based on the most positive aspect of Cranmer's eucharistic thought, namely, “the doctrine of the mystical union of Christ with the believing soul”. Thus, as H.A. Hodges wrote:

[For Cranmer,] by faith we live in Christ and He in us, and this not figuratively, but substantially and effectually, so that from this union we receive eternal life. When in the Eucharist we make our act of faith and thanksgiving, our union with Christ is strengthened and deepened; that is what is meant by saying that in this sacrament we 'feed' on Him. Cranmer reminds us of St Ignatius' phrase about the Holy Communion as the 'salve of immortality', and Dionysius' reference to it as 'deific', with other strong and graphic phrases from the Fathers to the same effect. It is this doctrine, this spirit, which finds expression in the Prayer Book liturgy. It is this which has kept alive a vein of eucharistic devotion in the Church of England through the most and apparently hopeless times. This is the core, around which it was ultimately found possible to reconstruct the whole edifice of Catholic eucharistic belief and practice. [10]

This further development in Anglican eucharistic thought and practice was chiefly the work of the so-called “Caroline Divines”, the sacramentally and patristically minded Anglican theologians from the time of Elizabeth I (1558) until the regicide of Charles I, “the Royal Martyr”, and after the restoration, during the rule of Charles II (1660-1667). Under Elizabeth, divines such as Richard Hooker and John Jewel had already begun to develop a distinctive, more moderate Anglican position. The Carolines continued this approach, both defending the Church of England as a truly “reformed catholic” church, but also working to make this “reformed catholicism” more tangible and apparent.

They sought, in the words of J.R.H. Moorman, “to build up in England a Church which should approach to the purity and devotion of the first centuries of the Christian era … a model of what a Christian Church should be, an example to the world.” In so doing, more than their Elizabethan predecessors, they appealed to [11] the Fathers of the Church (especially the Greek Fathers) and to the ancient Liturgies of the Church (particularly of the Oriental families). Caroline Anglican theology, according to G.W.O. Addleshaw, was “characterized by a veneration for the Fathers, by a wholeness finding its centre in the Incarnation and a massive learning.” [12]

In contrast to both continental Reformation and Counter-Reformation thought, the Carolines sought to work “in terms of patristic thought, more especially that of the Greek Fathers” – an approach which produced in the Carolines “something of the catholicity, the wide-mindedness, the freshness, the suppleness, and sanity of Christian antiquity.” Characteristic of this more “eastern” approach to the Faith [13] were these famous words prefacing the last will and testament of the Non-Juror[14] Bishop of Bath, Thomas Ken (1637-1711): “I die in the Holy, Catholic and Apostolick Faith, professed by the whole Church before the disunion of East and West.”[15]

Christopher Cocksworth observes that it was through the Caroline Divines – particularly Lancelot Andrewes, William Laud, Jeremy Taylor and John Cosin – that Anglicanism “fairly rapidly … recovered the notion of the instrumental function of the Eucharist together with a belief in an objective consecration as an essential part of the eucharistic action.” Eschewing what they perceived (perhaps not entirely[16] without justice) to be a Roman Catholic over-emphasis on the metaphysical aspects of the Eucharistic consecration , the Carolines instead devoted themselves to [17] explaining “the central Christological and soteriological issues of union with Christ and participation in his life — as Cranmer's prayer says, 'that we may evermore dwell in him, and he in us.'” [18]

Through an intense study of patristic texts and comparative liturgy, the Carolines, argues Addleshaw, recovered for Anglicanism “an understanding of the inner meaning of liturgy and its underlying principles, and a sense that liturgy had something to do with dogma and life.” This conviction was supported by the [19] scientific study of ancient Christian liturgies of the first four to five centuries, particularly the ancient Eastern liturgies (West Syrian, East Syrian, Coptic, Ethiopian, Byzantine, etc.).

For the Carolines, this work of restoring true Catholic worship was no mere human manipulation or antiquarianism. The Carolines were to explain their work in terms of the types of priestly and sacrificial worship in the Old Testament, and the ideal celestial liturgy of the the Apocalypse. Through their use of typology, writes

Benjamin Guyer, “the biblical past was connected to the English present, and heavenly worship made the model for earthly liturgy.”[20] William Beveridge (1637–1708), for instance, explains the restoration of proper liturgical praxis in his parish (St Peter's Cornhill, London) in terms of the restoration of the Altar and Temple under Judas Maccabeus (I Macc. 4):

For what the Altar and Temple were to the Jews then, the same will our Church be unto us now. Did they offer up their Sacrifices to God as Types of the Death of Christ? We shall here commemorate the said Death of Christ, typified by those Sacrifices. … Was the Temple an House of Prayer to them? So is the Church to us.[21]

In a very Dionysian passage, John Buckeridge (c. 1562-1631), Bishop of Rochester, spoke of liturgical restoration in terms of heavenly liturgy:

Praxis Ecclesiæ Triumphantis; the practice of the Triumphant Church in heaven; and this admitteth of no refusal; for heavenly things are the exemplars and patternes, to which earthly things must bee conformed. Is there a Tabernacle to bee made on earth? must not the modell thereof bee taken from heaven? Secundum formam in monte; thou shalt make it according to the forme shewed thee in the Mount. Is there a forme of life to be prescribed to men on earth? Is it not to bee guided by the rule of heaven? Thy will be done, Sicut in cælo, sic in terra, In earth as it is in heaven; the obedience of earth, must be squared by the line of heaven … And it it bee true, that the Church-government, the nearer it commeth to the Hierarchie of heaven, the more perfect, and absolute it is; it will also be true, that the neerer the worship, and Adoration of the Church militant resembleth the exact, and absolute pattern of the Triumphant Churches worship in heaven.[22]

The true father of the Caroline age in Anglican theology was Lancelot Andrewes, the “mystical theologian” par excellence of the English Church. Though legally bound [23] to worship according to Elizabeth's 1559 revision of the 1552 Prayer Book, the usage of his own private episcopal chapel was to become influential within the high church tradition. Andrewes restored many of the best features of the traditional pre-[24] Reformation order of Mass. The focal point of his chapel was a prominent, lavishly adorned, east-facing altar, separated from the rest of the church by an altar rail. Andrewes restored many of the old vestments, as authorized by the Elizabethan “Ornaments Rubric” as well as traditional liturgical vessels, including a Gothic style chalice and paten. Frankincense was offered, as in the old Mass, in a golden censer.

The ceremonial of his chapel also brought back many rituals of eucharistic offertory, including an offertory of the eucharistic gifts clearly differentiated from the reception of alms and the old ceremony of mixing water with the wine. Andrewes' doctrine of eucharistic offertory was vividly illustrated in the image which hung above his altar, depicting the story of Abraham and Melchisedech, and thus [25] recalling the Supra quæ propitio of the Roman Mass. [26]

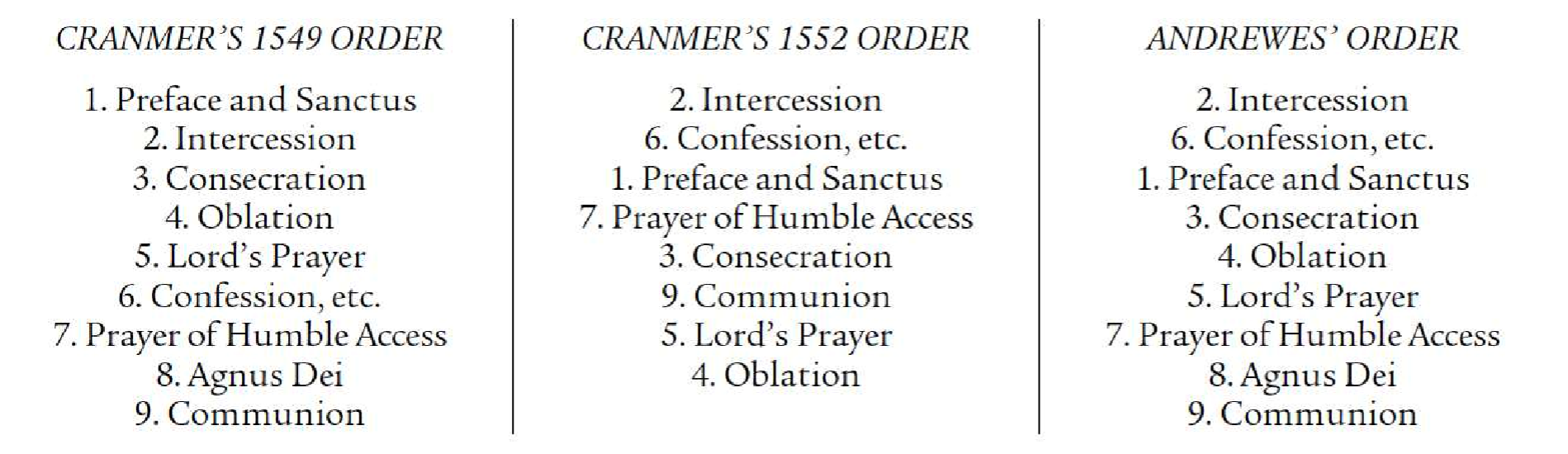

Within the Prayer of Consecration, Andrewes restored the old manual acts, retained in 1549 but omitted in 1552. Perhaps more importantly for the development of the Anglican Liturgy, Andrewes skillfully reordered the prayers of the 1552/1559 Liturgy, so as to transform it from being a series of Communion devotions into a true Liturgy, after the patterns of Christian antiquity. The following chart shows Andrewes' order as compared to 1549 and 1552:

Further, Andrewes had no scruples about the occasonal replacement of the somewhat sparse, flat Cranmerian Prayer of Oblation (“O Lord and heavenly Father, we thy servants entirely desiring thy fatherly goodness”) with the Anamnesis of the Liturgy of St Basil, one of the most stupendous in all of Christendom. Finally, it is [27] entirely possible that Andrewes restored prayer for the dead in the context of the eucharistic prayer, since in his private devotions he prayed for the departed, and affirmed in his apologia to Cardinal Perron that the Eucharist is a sacrifice offered for the quick, the dead, and even the unborn. [28]

Though the liturgical thought and practice of Bishop Andrewes was the exception, rather than the rule, within the Church of England, his Caroline successors were greatly influenced by Andrewes' balanced approach. His direct influence is seen immediately in William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury under Charles I, and through Laud, in the creation of the first Scottish Liturgy of 1637, ill-fated but significant as the first official, substantial return to something approaching the original 1549 order.[29]

Archbishop Laud, following Jewel, Hooker and Andrewes, sought to show the Church of England to be truly “catholic and reformed” in doctrine, liturgical practice and discipline. In advocating such a “reformed catholic” position, he came into bitter conflict with Calvinists and Puritans, a conflict which would later claim his life and that of his king, Charles I. Laud firmly and unapologetically believed and taught that the Eucharist was the true, proper Christian Sacrifice, offered up in union with the one Sacrifice of Christ upon the Altar of the Cross.

According to his reading of the Prayer Book Liturgy, Laud enumerated three distinct kinds of sacrifice made within the Eucharistic Liturgy:

For, at and in the Eucharist, we offer up to God three sacrifices: One by the priest only; that is the commemorative sacrifice of Christ's death, represented in the bread broke and wine poured out. Another by the priest and the people jointly; and that is, the sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving for all the benefits and graces we receive by the precious death of Christ. The third, by every particular man for himself only; and that is, the sacrifice of every man's body and soul, to serve Him in both all the rest of his life, for this blessing thus bestowed on him. [30]

Although he denied that the Body and Blood of Christ themselves were offered by the priest, Laud did hold that the Liturgy must clearly reflect the fact that the bread and wine are offered upon the altar by the priest. Thus Laud, following Andrewes, made a striking departure from Cranmer in attaching great importance to the act of offering the eucharistic elements, even though such an act had been removed from the Prayer Book in 1552. In answer to his Puritan enemies at his trial, Laud readily admitted his dissent from the practice of 1552: “As for the oblation of the elements, that's fit and proper; and I am sorry, for my part, that it is not in the Book of England.”[31]

Laud also recovered a notion of true and real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, another major departure from the doctrine of Cranmer. Although vehemently denouncing what he believed to be the Roman Catholic teaching on Transubstantiation, Laud argued that in the Eucharist, the worthy communicants really and truly partook of Christ's true, spiritual, and sacramental presence in the consecrated eucharistic elements. Influenced by the liturgies of the Christian East, Laud also attached particular importance to the role of the epiclesis (the slightly odd version, invoking both “the Word” (presumably Christ) and the Holy Spirit went missing from the 1552 order), as that which calls down the power of God to transform the elements so that in use they would be received as the true sacramental Body and Blood of Christ.

Unfortunately, Laud's teaching on the Eucharistic Presence still had a “receptionist” ring to it. Basing his argument upon the phrase ut fiant nobis in the prayer Supplices te rogamus in the Roman Canon, Laud argued that “they 'are to us', but are not transubstantiated in themselves, into the Body and Blood of Christ, nor that there is any corporal presence, in or under the elements.” Consequently, Laud did not [32] believe that any sort of adoration was due to the consecrated elements. Even though, like Cranmer, Laud (in the words of W. Jardine Grisbrooke) “still thinks within the terms of the medieval dilemma that imprisoned the theologians of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation alike,” his eucharistic doctrine is still “poles apart from that of Cranmer.” Laud clearly “believed in a real presence mediated through the bread and wine, and believed also that these elements were offered to God by the priest.” [33]

As with other Caroline divines, Laud's moderate Eucharistic realism was incarnated in his liturgical practice, especially in the restoration of the centrality and sacrality of the altar, and its ornamentation. “The altar”, he said against the Puritans, “is the greatest place of God's residence upon earth, greater than the pulpit for there 'tis Hoc est corpus meum, this is my body; but in the other it is at most but Hoc est verbum meum, This is my word.” The horror of the Puritans at these developments is vividly expressed in a clergyman of that party, Peter Smart, in a sermon against ceremonial practices at Durham Cathedral under Richard Neile (1562-1640):

Before, we had ministers, as the Scripture calls them, we had Communion-tables, we had sacraments; but now we have priests, and sacrifices, and altars, with much altar furniture and many massing implements. … If religion consist in altar decking, cope wearing, organ playing, piping and singing, crossing of cushions and kissing of clouts, oft starting up and squatting down, nodding of heads and whirling about till their noses stand eastward, setting basins on the altar, candlesticks, and crucifixes, burning wax candles in excessive number when and where there is no use of lights; and what is worst of all, gilding of angels, and garnishing of images, and setting them aloft … if I say, religion consist in these and such like superstitious vanities, ceremonial fooleries, apish toys, and popish trinkets, we had never more religion than now. [34] Although Laud himself continued to use the 1552 Liturgy as reformed by Elizabeth (albeit slightly altered, enriched, and with an intent very different from that of Cranmer), the Laudian approach to eucharistic doctrine came to be enshrined officially in the compilation of the first Scottish Book of Common Prayer in 1637. The Eucharistic order of this Prayer Book, says Grisbrooke, “marks the first authoritative move on the part of an Anglican hierarchy to cast aside the liturgical and doctrinal heritage of Cranmer.” [35]

The Scottish Liturgy of 1637 was an extensive revision of the Prayer Book service, casting aside the most Protestant structural and verbal features of 1552 in favor of a restoration of 1549 usage. These changes clearly reflected “a theology that connected the Eucharistic elements with Real Presence and Sacrifice.” The chief architect of[36] the 1637 revision was not Laud himself (despite the popular reference to “Laud's Book”) but James Wedderburn (1585-1639), Bishop of Dunblane. Wedderburn, erudite patristic and liturgical scholar, was a “Scottish Canterburian,” in favor with Charles I and Archbishop Laud, and a foe of Scottish Presbyterianism.

Initially, the two bishops, already in agreement concerning eucharistic doctrine, favoured different practical approaches to liturgical reform. Laud would have simply introduced the English Liturgy into Scotland, while Wedderburn desired a wholesale restoration of the 1549 Mass. Soon, however, they agreed on a compromise. Wedderburn was able to convince Laud of the desirability of extensive changes in the direction of 1549, while Laud succeeded in preserving some of the current English order. [37]

What resulted is arguably a far more logical and balanced anaphora than the original 1549 order. Wedderburn was able to skillfully restore important aspects of the 1549 structure and wording in order to convey an unmistakable belief in Real Presence and Eucharistic Sacrifice. The 1549 epiclesis was reintroduced, with the addition of three short words but powerful words which connected the elements with Christ's Body and Blood: “so that we receiving them … may be partakers of the same his most precious Body and Blood.” Rubrics for the manual acts at the Words of Institution were restored.

The Oblation, or anamnesis, was reinserted within the Prayer of Consecration itself, with some choice differences in wording, linking the “holy gifts” on the altar with the celebration of “the Memorial which thy Son hath willed us to make; having in remembrance his blessed Passion, mighty Resurrection, and glorious Ascension…” The words “the most precious Body and Blood of thy Son Jesus Christ” were restored and connected with Cranmer's majestic phrase, “Made one body with him, that he may dwell in them, and they in him.”

Outside of the canon itself, the orignal offertory rubrics and language were restored; the celebrant is directed to “humbly present [the oblation of bread and wine] before the Lord, and set it upon the holy Table.” The congregation was spoken of as being assembled to “celebrate the commemoration of Christ's Death and Sacrifice.” The[38] Prayer of Humble Access was moved back to its proper place, after the Consecration and before Communion. Likewise, the Lord's Prayer (with the addition of a doxology) was restored as the ancient climax of the Canon. Finally, the original 1549 Words of Administration were restored, without the addition of the heterodox receptionistic formulas of 1552.[39]

The attempted heavy-handed imposition of the 1637 book upon the Presbyterian majority in Scotland was violently resisted. When the services were first celebrated at St Giles' Cathedral in Edinburgh, a riot broke out to cries of “The Mass is entered amongst us!” The incident signaled the beginning of the massive Puritan[40] revolution against the monarchy and the Church of England, which would result in the executions of both Charles I (in 1649) and Archbishop Laud (in 1645) under Oliver Cromwell's reign of terror.

It did not help in the least that the name of the new liturgy had become associated with Laud, the English scourge of Puritanism, and with English supremacy. Although he himself had always used the official Liturgy of England, at his trial Laud did not deny his admiration for the 1637 Liturgy as a return to ancient Christian doctrine and practice:

And though I shall not find fault with the order of the prayers as they stand in the Communion-book of England (for, God be thanked, 'tis well;) yet, if a comparison must be made, I do think the order of the prayers, as now they stand in the Scottish Liturgy, to be the better, and more agreeable to use in the primitive Church; and I believe, they which are learned will acknowledge it. [41]

Though Scotland itself immediately rejected the new Prayer Book, the stage had nevertheless been set for all subsequent reforms of the Anglican Eucharistic Liturgy in the direction of both 1549 (interpreted against the intentions of its framer) and Eastern liturgical sources. Several later Anglican liturgical reforms, inspired by the examples of the Carolines, took their inspiration from 1637. The stage had been set for subsequent movements towards Catholic faith, practice, and unity, such as those of the Non-Jurors, the Oxford Movement, the Ritualists, and ultimately, in our time the small yet prophetic witness of the Personal Ordinariates in full communion [42] with the Mother Church of the Ecclesia Anglicana.

This article is based upon parts of the author's M.Div. thesis concerning the historical background of the “Liturgy of Saint Tikhon”, an Eastern Orthodox revision of the 1928 American Liturgy as supplemented in sources such as The American Missal (1952). Thanks to Prof. William Tighe for assistance in preparing this revision. ↩︎

Even very advanced Anglo-Catholics would maintain a certain measure of dependence upon him, as the various editions of the English Missal (W. Knott & Sons.) show. Cyril Tomkinson (1886-1968), vicar of All Saints, Margaret Street, London, would describe his liturgical ideals thus: “music by Mozart, décor by Comper, choreography by Fortescue, but, my dear boy, libretto by Cranmer” (quoted in The Oxford Handbook of the Oxford Movement [2017], p. 521.) ↩︎

Quoted in Henry Chadwick, Early Christian Thought and the Classical Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1966), p. 95. ↩︎

Eucharist: Theology and Spirituality of the Eucharistic Prayer. Charles Underhill Quinn, translator. (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1968), p. 417. ↩︎

Ibid, p. 414. ↩︎

The Shape of the Liturgy (New York: Seabury Press, 1982), p. 659. E.C. Ratcliff comes to essentially the same conclusions as Dix but in a more nuanced manner; see “The English Usage of Eucharistic Consecration 1548-1662,” originally published in Theology LX:444 (June 1957), pp. 229-236, and LX:445 (July 1957), pp. 273-280; and “The Liturgical Work of Archbishop Cranmer,” Journal of Ecclesiastical History, VIII:2 (October 1956), pp. 189-203. ↩︎

W. Jardine Grisbrooke. Anglican Liturgies of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. (Alcuin Club Collections No. XL). (London: SPCK, 1958), p. xiii. ↩︎

The High Church Tradition: A Study of the Liturgical Thought of the Seventeenth Century (London: Faber and Faber, [no date]), p. 63-64. ↩︎

Grisbrooke, p. xiii. ↩︎

Anglicanism and Orthodoxy: A Study in Dialectical Churchmanship. (London: SCM Press, 1955), 18-19. ↩︎

Moorman, J. R. H. A History of the Church in England. 3rd edition. (Harrisburg, PA: Morehouse, 1986), p. 225. ↩︎

Addleshaw, p. 25. ↩︎

Ibid, p. 26. ↩︎

That is, one of the English churchmen who refused to swear an oath of allegiance to the Dutch usurper William of Orange, who captured the crown in 1689. ↩︎

Quoted in Moorman, p. 234. ↩︎

“Eucharistic Theology”, in Kenneth Stevenson and Bryan Spinks (editors), The Identity of Anglican Worship (Harrisburg, PA: Morehouse, 1991), pp. 50. ↩︎

Jeffrey H. Steel, in his doctoral thesis, Eucharist and Ecumenism in the Theology of Lancelot Andrewes (1555-1626): Then and Now (2012), characterises Andrewes' eucharistic doctrine as objective but non-Roman in the sense of “Cappadocian” and “Transelementationalist”: “What Andrewes accomplished was a liberal drawing from both East and West within his ceremonial and sacramental realism that would wed the traditions of a broken Church in the unity seen in the first five centuries […] What Andrewes accomplished was a liberal drawing from both East and West within his ceremonial and sacramental realism that would wed the traditions of a broken Church in the unity seen in the first five centuries.” (p. 223). ↩︎

Cocksworth, p. 54. ↩︎

Addleshaw, p. 18-19. ↩︎

The Beauty of Holiness: The Caroline Divines and Their Writings (Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2012), p. 23. ↩︎

A Sermon Concerning the Excellency and Usefulness of the Common Prayer (1682), p. 1. ↩︎

Quoted in Guyer, pp. 27-28. ↩︎

Hence Russian Orthodox theologian Nicholas Lossky's now classic study Lancelot Andrewes, the Preacher (1555-1626): The Origins of the Mystical Theology of the Church of England, trans. Andrew Louth (Oxford University Press, 1991). ↩︎

Marianne Dorman, “Andrewes and English Catholics' Response to Cranmer's Prayer Books of 1549 and 1552.” Project Canterbury. <_resources/2024/07/23/205845/80510.pdf>, p. 2. ↩︎

Ibid, p. 3-4. ↩︎

“Vouchsafe to look upon them with a merciful and pleasant countenance: and to accept them, even as thou didst vouchsafe to accept the gifts of thy servant Abel the Righteous, and the sacrifice of our Patriarch Abraham: and the holy sacrifice, the immaculate victim, which thy high priest Melchisedech offered unto thee.” (trans. from the Missale Anglicanum, 1958 ed.). ↩︎

“Therefore, O Master, we also, remembering [Christ's] saving passion and life giving Cross, His three-day burial and resurrection from the dead, His ascension into heaven, and enthronement at thy right hand, O God and Father, and His glorious and awesome second coming, we offer to thee these gifts from thine own gifts in all and for all.” ↩︎

Dorman, p. 5-6. ↩︎

Ibid, p. 8-9. ↩︎

“A Relation of the Conference between William Laud and Mr. Fisher the Jesuit”, in The Works of the Most Reverend Father in God, William Laud, D.D., Sometime Lord Archbishop of Canterbury, vol. II (Oxford: John Henry Parker, 1849), pp. 339-341. ↩︎

Ibid, vol. 3, p. 359. ↩︎

Ibid, p. 116. ↩︎

Grisbrooke, p. 17. ↩︎

Sermon of 27 July 1628, published as The Vanitie and Downefall of Superstitious Popish Ceremonies; quoted in Mackintosh, pp. 122-123. ↩︎

Ibid, p. 18. ↩︎

Edward P. Echlin, The Anglican Eucharist in Ecumenical Perspective: Doctrine and Rite from Cranmer to Seabury. (New York: The Seabury Press, 1968), p. 109. ↩︎

Prayer Book Studies, p. 74. ↩︎

Echlin, p. 122-125. ↩︎

“The Body of our Lord Jesus Christ, which was given for thee, preserve thy body and soul unto everlasting life. [Take and eat this in remembrance that Christ died for thee, and feed on him in thy heart by faith, with thanksgiving.]” — “The Blood of our Lord Jesus Christ, which was shed for thee, preserve thy body and soul unto everlasting life. [Drink this in remembrance that Christ's Blood was shed for thee, and be thankful.]” ↩︎

Moorman, p. 228. ↩︎

The History of the Troubles and Tryal of the Most Reverend Father in God and Blessed Martyr William Laud, Lord Archbishop of Canterbury, Vol. I (London: Ri,. Chiswell, 1695), p. 115. ↩︎

I have in mind here what Aidan Nichols OP wrote concerning the existence of the Eastern Catholic Churches as an eschatological sign: “[O]n the supposition that a totally reunited Christendom is not, intrahistorically, a realistic hope, such unity [for which Christ prayed] will be seen most fully in the representative gathering of apostolic churches and traditions around the figure of Peter, represented in his vicar, the Roman bishop. … [T]he fact that most Eastern Catholic churches are minoritarian, and some glaringly so, does not constitute a problem. The dignity of their eschatological significance is unaffected by the numbers game.” (Rome and the Eastern Churches: A Study in Schism, 2nd edition [San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2010], pp. 19-20). ↩︎